There is a fascinating, albeit unusual, eclipse phenomenon that occurs on the daylight side of the Earth. Moreover, this event applies to occultations of stars, although it’s a topic for another occasion. It refers to the moment of “earliest maximum eclipse” and “latest maximum eclipse”, which don’t occur precisely in the place where the edge of the Moon’s penumbra reaches the Earth’s limb (Meeus, 2007). Near the most extremal locations of solar eclipse, where the Sun and Moon are relatively low above the horizon, the maximum eclipse for a given magnitude of the partial eclipse may occur above the horizon up to about 2 minutes before it occurs westward at sunrise at the horizon, and conversely up to 2 minutes after it occurs eastward at sunset at the horizon (Nufer, 2011). Unlike the “airless” Earth considered for the calculation of the effect above, this article presents an analogous “strange effect” that appears to occur during solar eclipses, accounting for the Earth’s atmosphere on the night side. The primary moment, at which everything happens, occurs when the lunar shadow axis is tangent to the Earth’s globe. There are two moments like this throughout the entire eclipse event – at sunrise and sunset. To better understand this phenomenon, the Earth can be imagined as a transparent sphere, with the atmosphere playing an analogous role. Unlike the ground, which casts a shadow and limits the visibility of umbra behaviour on the other side of the globe, the atmosphere doesn’t. In turn, an observer can see the very last moment of the apparent movement of the umbra on the Earth’s dark side. This specific umbra behaviour within the Earth’s shadow zone will be explained in detail in a later text. At this moment, several explanations are presented in the graphs and movies below. In fact, the phenomenon was never observed, and all the visualisations are based on the Stellarium ShowMySky mode and Space Engine 0.99 software, which should help you understand this remarkable occurrence before you set out for the observation. At first, worth attention are graphs below, which present how the umbra behaves against the Earth’s surface at its various positions (Pic. 1) and at the moment, when it becomes tangent to the Earth’s surface at the most extreme moments of solar eclipse (Pic. 2).

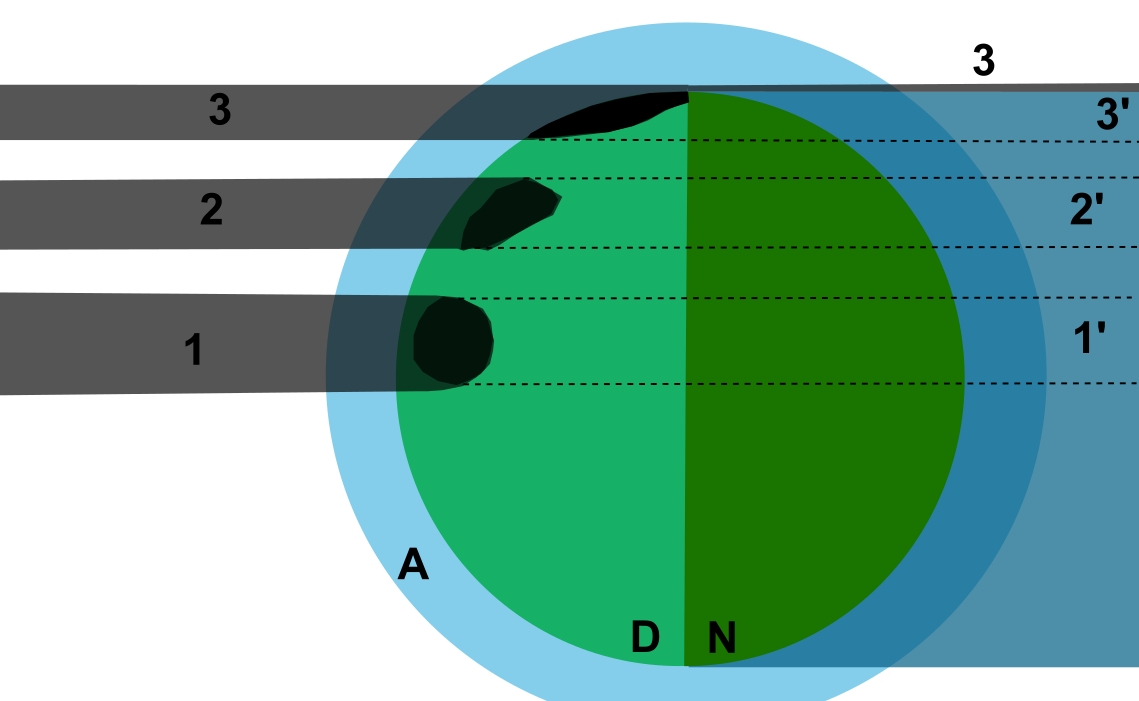

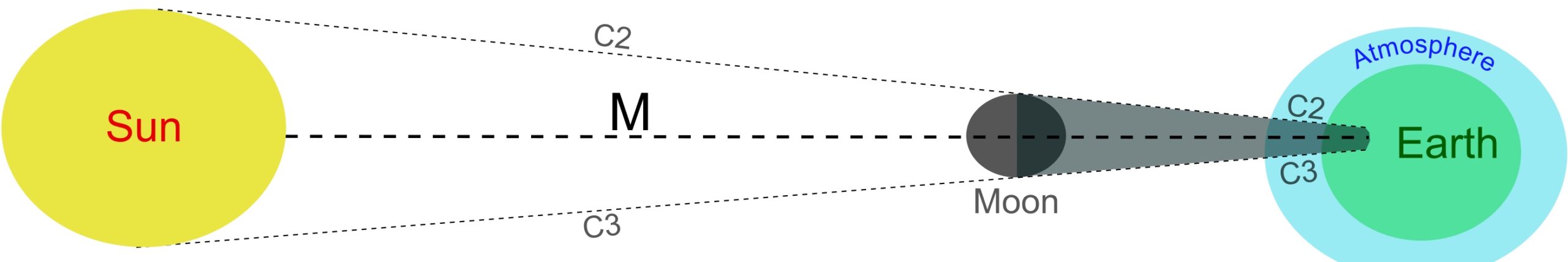

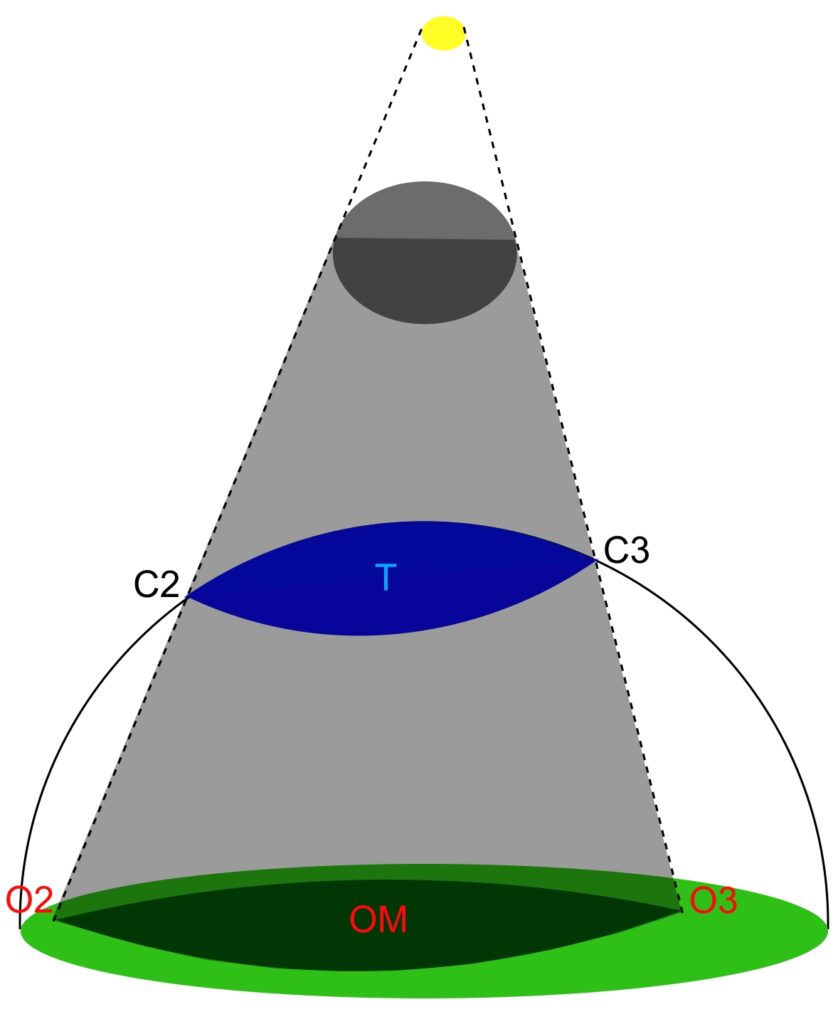

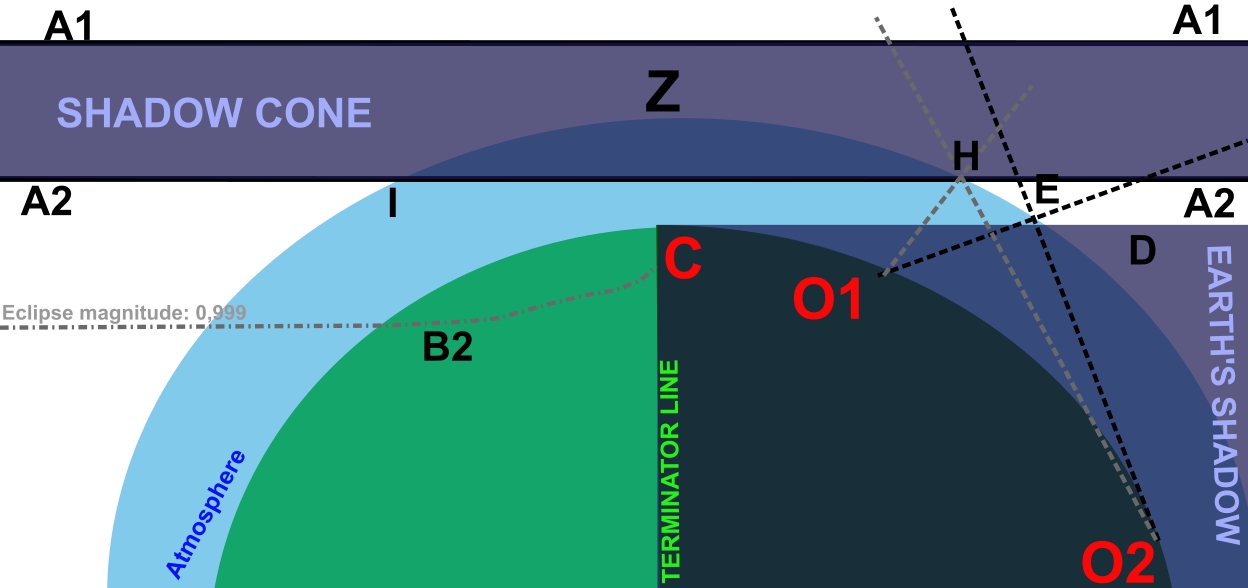

As the solar eclipse is observed on the daylight side of the Earth, the umbral (or alternatively antumbral) cone falls perpendicularly or diagonally onto the Earth’s surface, depending on the position of the Sun above the horizon when the eclipse occurs. This is fairly understandable. However, if we want to understand the strange effect that occurs when the Sun is below the horizon, the hypothetical projection of the umbra is noteworthy here. Accordingly, in situation 1, during a near-zenith eclipse, the umbra hits the Earth’s surface perpendicularly. Considering its theoretical way with assumption, that the Earth would be transparent, the umbra is visible on the opposite side of the globe (1′). The same applies when the umbral cone hits the Earth during an eclipse at a lower altitude above the horizon (2). It’s typical for the morning and the afternoon. Despite the oval shadow projection on the Earth’s surface, the cone remains cylindrical as far as the transparent Earth is concerned. Again, it passes the Earth in the same position, but on the other side (2′). Both positions are determined by the altitude of the Sun above the horizon, which marks, in other words, the angular distance to the very top of the Earth’s sphere. In practical terms, if the umbral cone hits the daylight side of the Earth at an altitude of 10°, it would appear at solar depression of 10° on the other side of the globe. Finally, we have the moment when the umbra approaches the terminator. This is the situation when the cone becomes tangent to the Earth’s surface (3). When the umbra edge approaches the terminator line, it starts to be visible at the antisolar point in the same moment (3) whilst the opposite edge of the umbra is geometrically still below the horizon (3′). This is because the Earth is a sphere, likewise the atmosphere. The umbra advances into the terminator, following Earth’s shadow through the atmosphere until it leaves the atmosphere completely and enters space. The more complex illustration below explains this moment precisely (Pic. 2).

We need to consider Earth as an opaque body and its atmosphere as a transparent body, allowing the umbra to pass through.

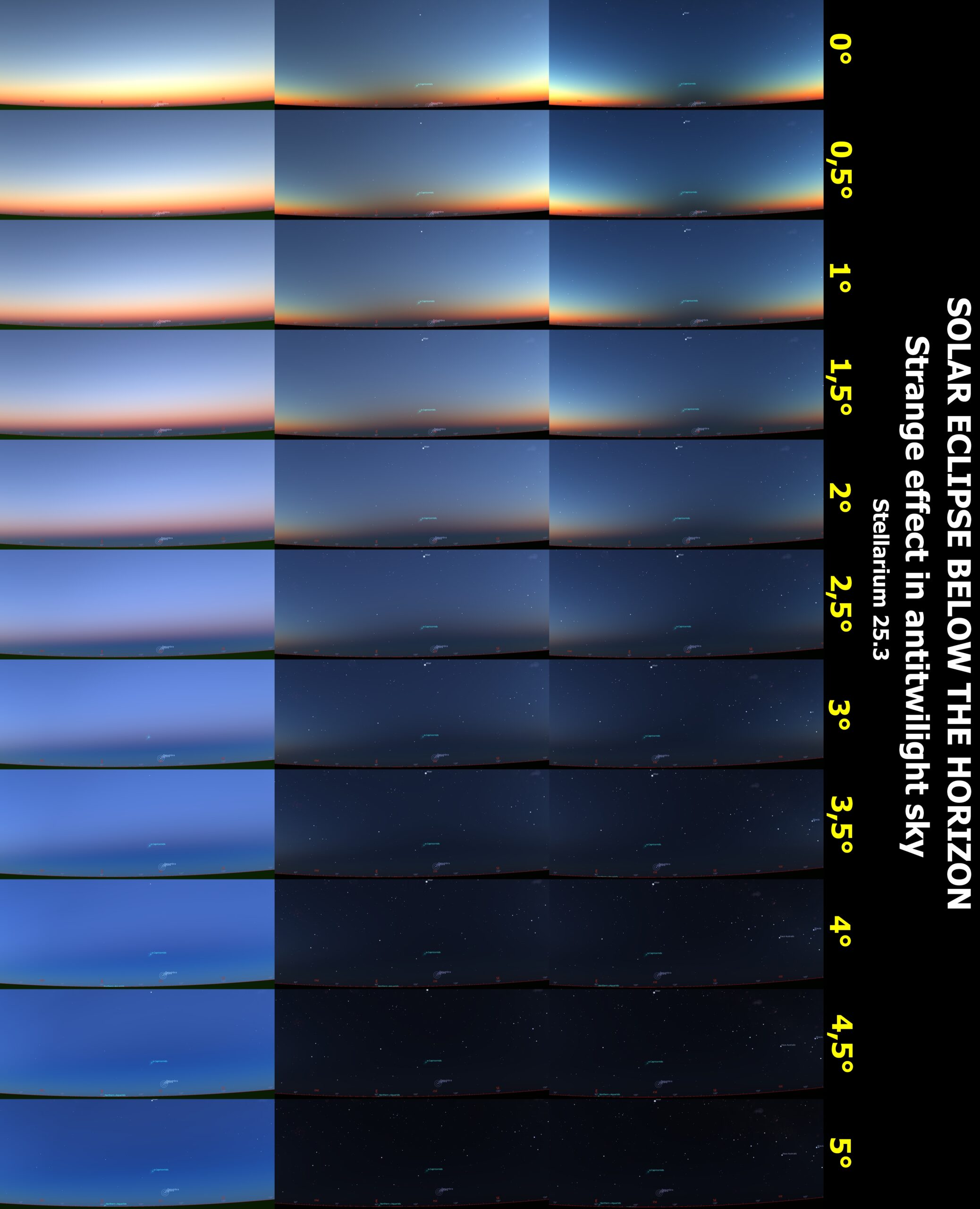

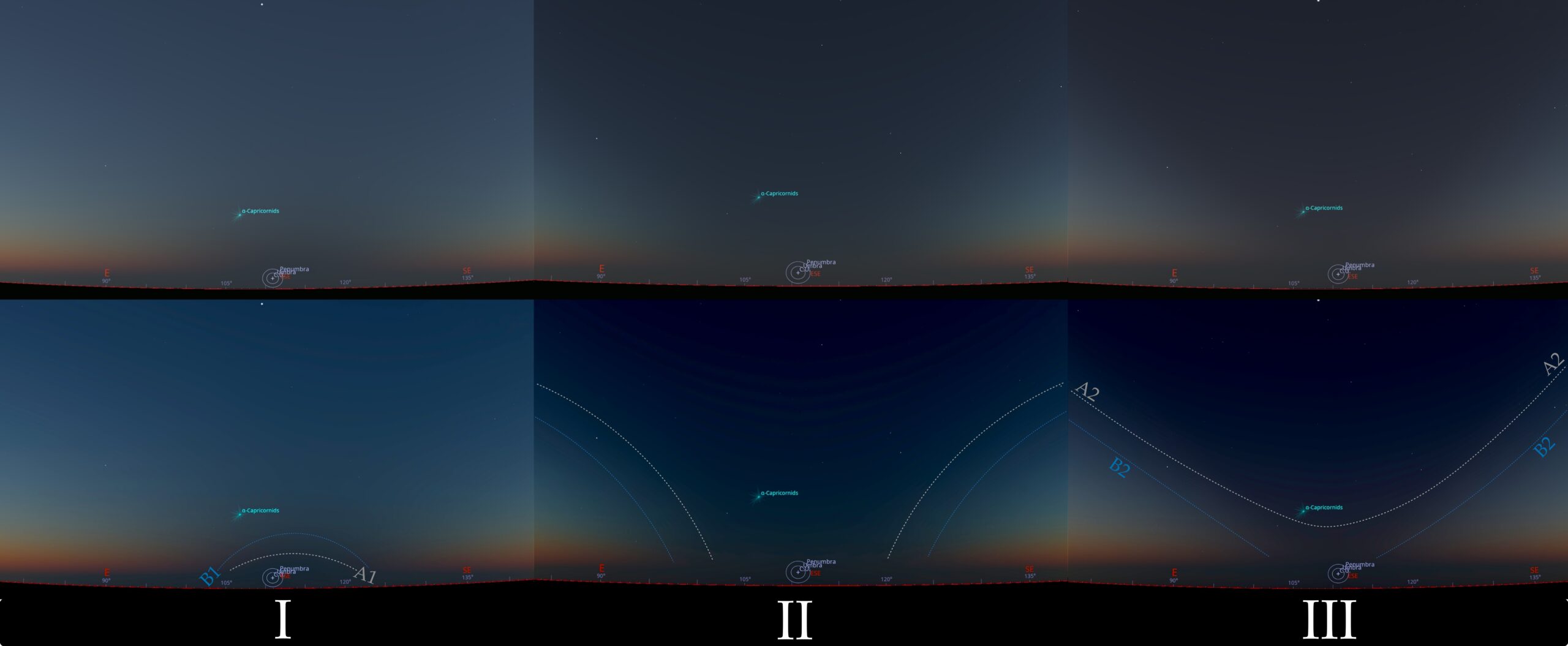

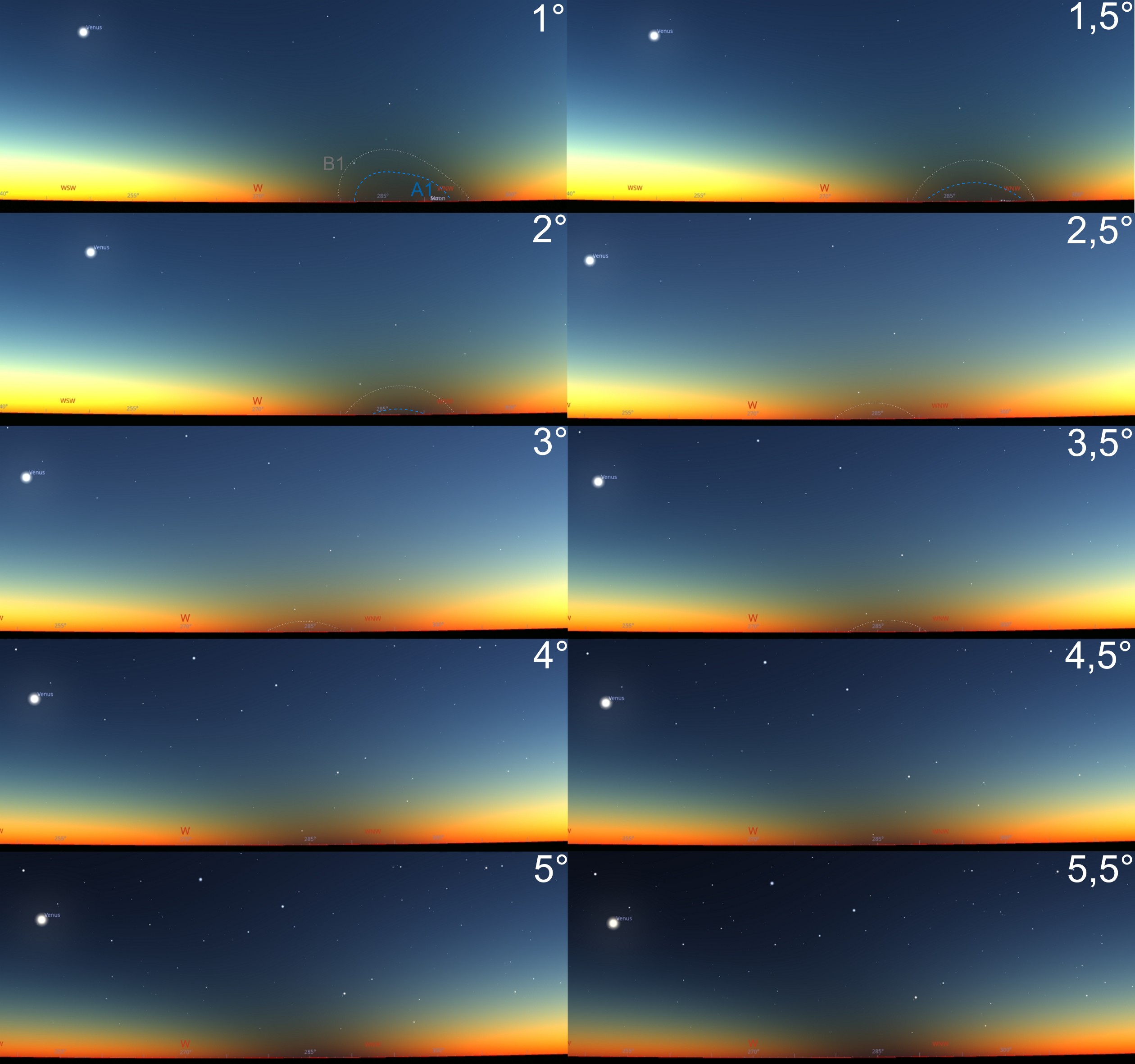

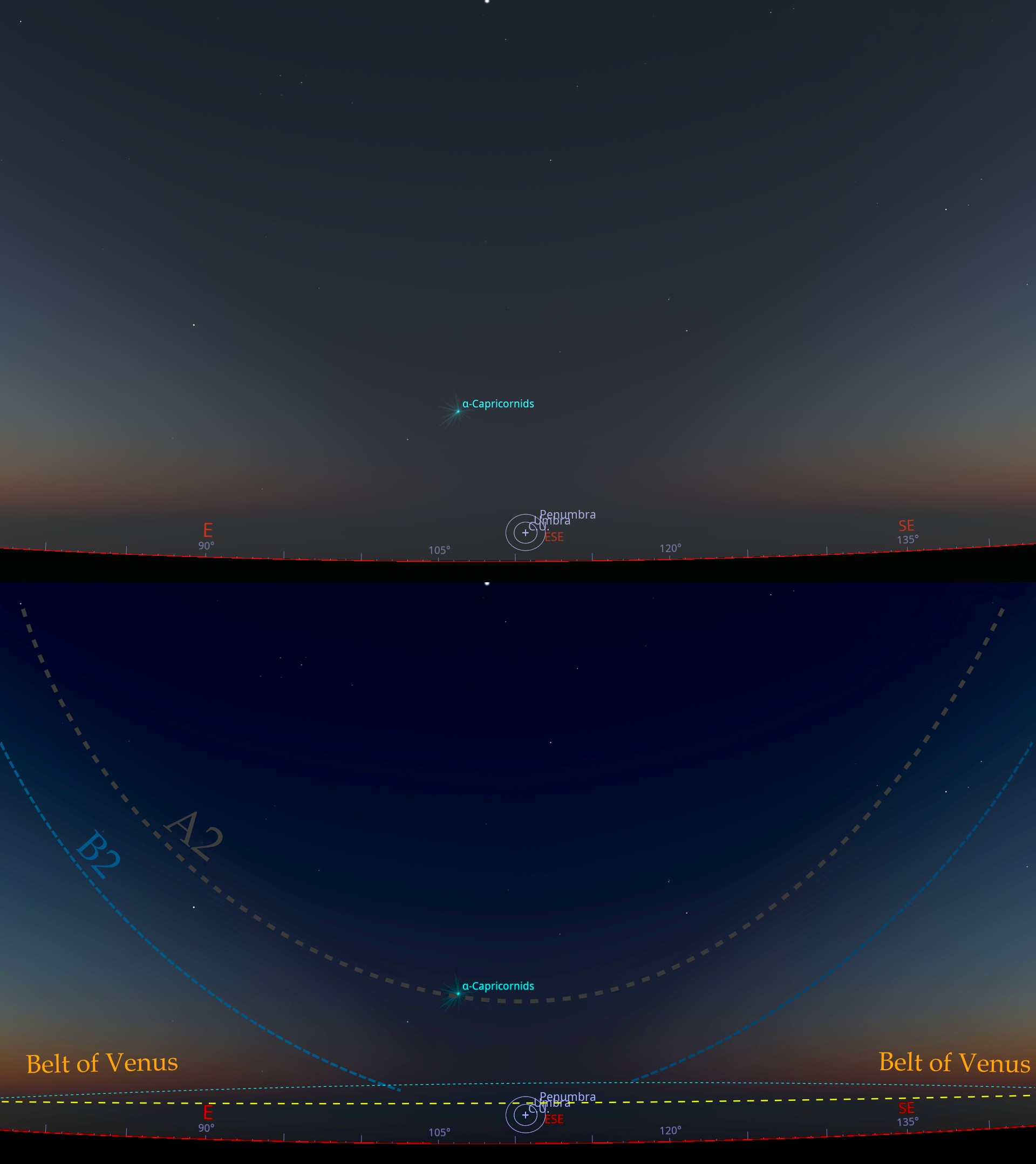

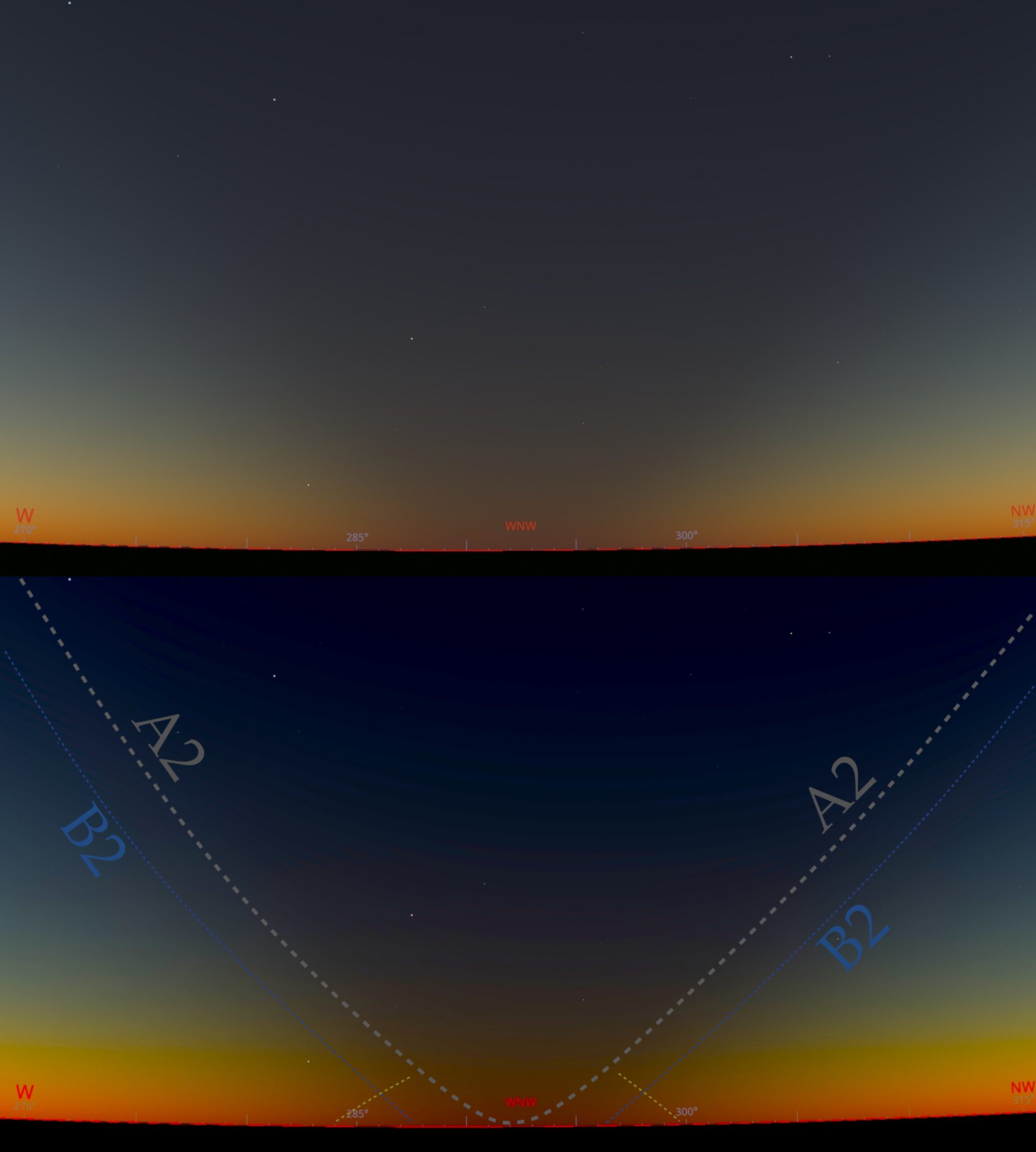

From the geometrical point of view, the moment at which the umbral cone is tangent to the Earth’s surface is only when it hits the terminator line. As mentioned earlier, such a situation occurs twice along the entire eclipse path – roughly at sunrise and sunset. Considering the umbral cone as a thin cylinder, only one side (A1) passes the terminator line, whereas the other side (A2) is still being projected on the Earth’s surface. As the A1 umbra limit is observed at the terminator line, it doesn’t stop on the Earth’s ground. It becomes visible beyond in the transparent atmosphere to the point E and further into the space. The line C – E indicates the same moment of the sunset. Since point C represents the ground-based position, point E corresponds to the moment of sunset observed at the altitude of the upper limit of Earth’s atmosphere, with the dip of the horizon applied. As discussed in previous articles, we consider an altitude of approximately 40km above ground, above which the daylight sky is completely dark. Because the line C – E indicates the moment of sunset, it points out the edge of Earth’s shadow (D) and thereby the umbra limit continued from the terminator line to the space (A1). At the same time, the atmosphere between lines A1 and B1 is affected by the magnitude of the almost-total eclipse, resulting in an abrupt decrease in illumination. For an observer standing roughly at the terminator line in point C, the zenith sky Z is still outside of the Moon’s shadow, and even outside the auxiliary line of the almost-total eclipse magnitude of 0,999 (B1), which by that makes it the brightest against the sections located at solar and antisolar directions. Since the opposite side of the umbra is projected on the Earth’s surface shortly before sunset (or after sunrise) (A2), the same happens to the curves of the same eclipse magnitude (B2). For an observer located at the point C, the totality begins exactly at geometrical sunset (G), but because at this location the umbral cone is tangent to the Earth’s surface, it lies parallel to the Earth’s shadow edge and becomes visible at the same time on the horizon at antisolar direction (E). The Moon’s shadow, viewed from the perspective of sunset, is parallel to the ground, making it visible simultaneously from both sides of the sky along the line G-C-D. This effect is best visible at the smallest solar depression, when the twilight wedge emerges in the direction opposite to sunset. From the perspective of another observer, located within deep civil twilight (O1), the effect will be visible partially. The twilight wedge will be “bulging” at the opposite azimuth to the Sun, because this observer is able to see the edge of the shadow cone at point E and significant brightening of the sky at point F. The section of the sky between lines O1 – F and O2 – E will fall under almost-total solar eclipse conditions and make the twilight wedge bow-fronted appearance. The observer O2, located within the nautical twilight zone, won’t be fortunate enough to see this effect, as, from his perspective, the point F is beneath the horizon. This is probably why I couldn’t detect this effect during my observation in Spain in 2024. The sky at solar azimuth probably looks darker than in other directions. Both observers (O1 and O2) are unable to see the umbra approaching at solar azimuth because it occurs under the horizon. I realise that this tough explanation isn’t enough for you to understand the effect, so I’ve prepared several instances generated by the Stellarium Show My Sky mode, that apply to the changes of solar depression by 0,5°. Firstly, we can have a look at solar azimuth, which is the easiest to understand (Pic. 3).

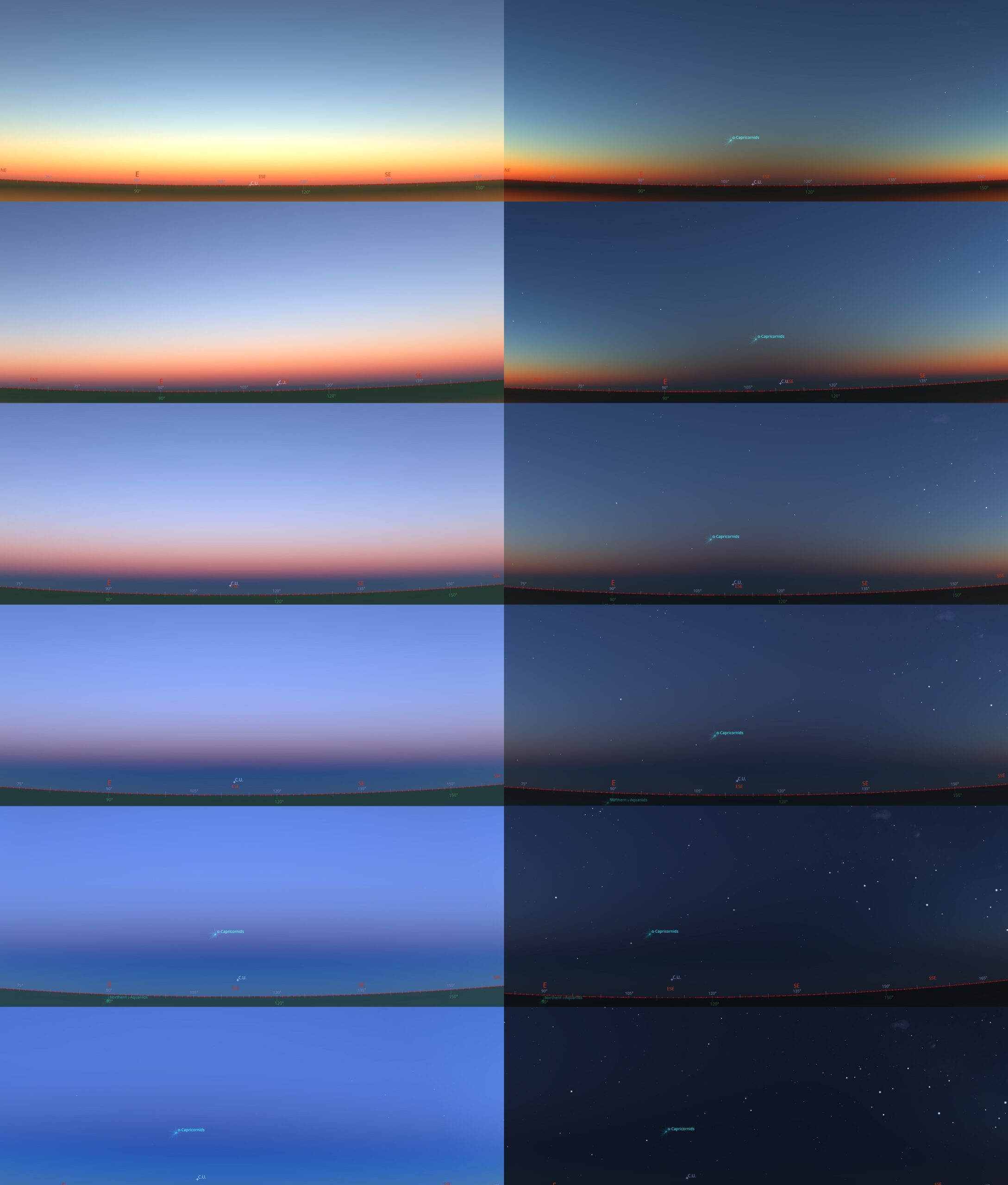

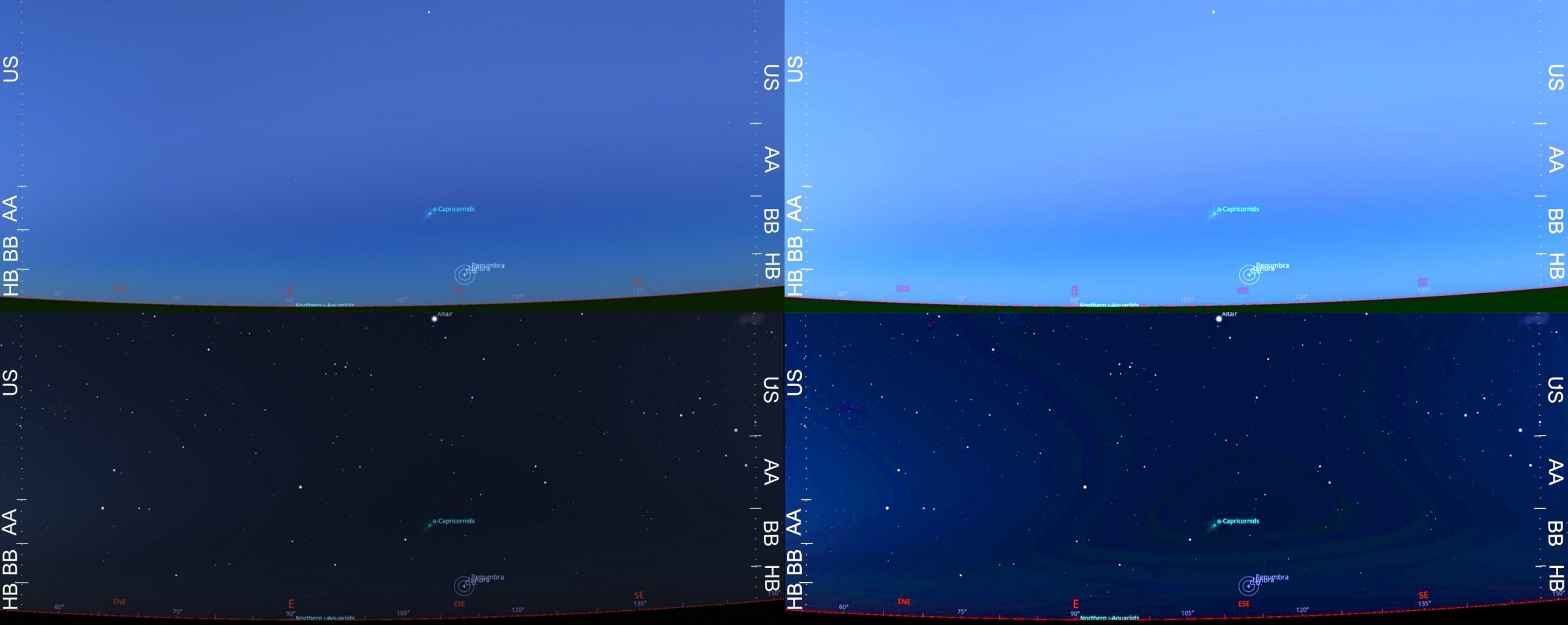

The image above (Pic. 3) projects the 2nd contact in the Mediterranean region on August 12, 2026, within the zone of civil dusk. The instances represent locations near the extended centerline of the eclipse path. In any situation, the 2nd and 3rd contacts indicate the beginning and end of totality. The simplest definition explains a total solar eclipse as an event in which the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth. Considering this simple definition in a more professional sense, the Moon passes between the Sun and the observer’s location. The straight line connecting the Sun, Moon and observation venue passes through the Earth’s atmosphere before it ends on the ground. Since the portion of the Earth’s atmosphere is located on this line, it becomes shadowed in exactly the same moment at which the 2nd contact is reported from the observation place. In practise, it leads to the following rule:

The celestial position of the Sun at 2nd contact makes the sky simultaneously shadowed at that direction. Any time after the 2nd contact means a shadowed sky at the exact solar direction. It occurs until the 3rd contact.

It’s fairly clear in the graphs below (Pics. 4 and 5).

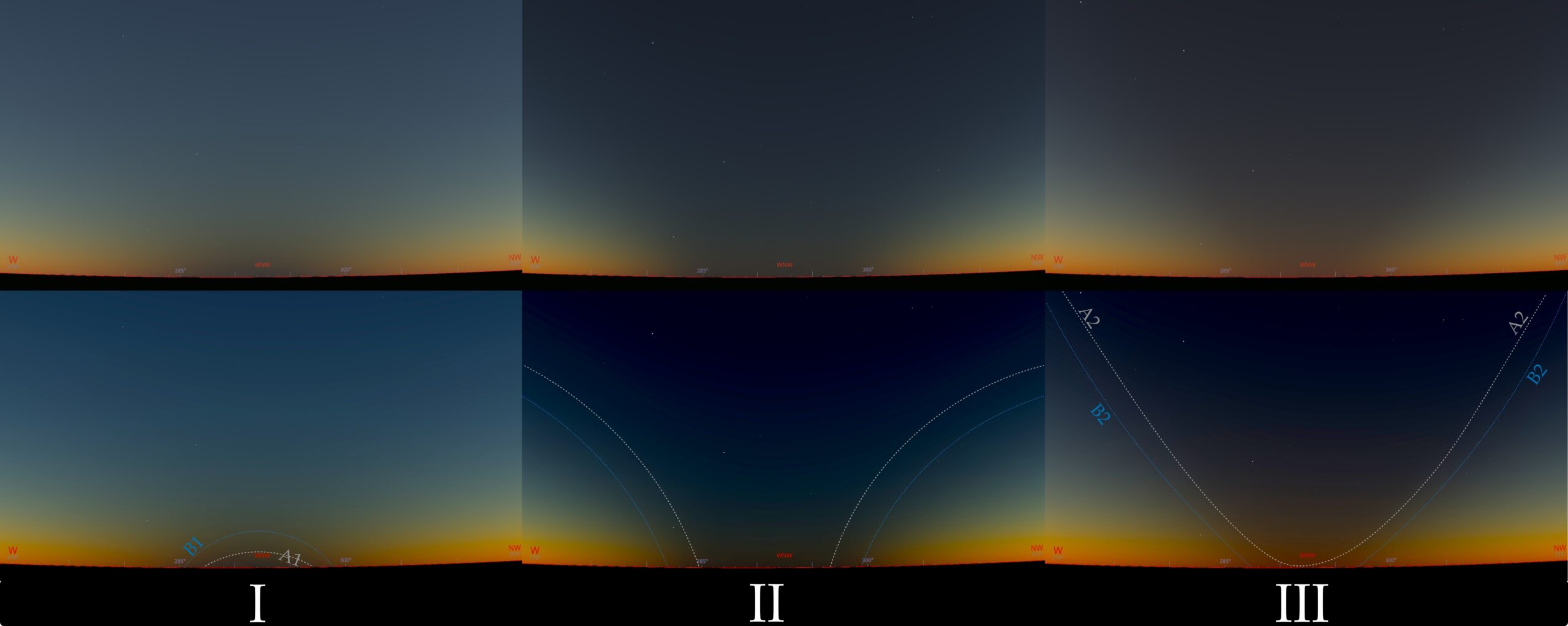

The main line M covers the key definition of a solar eclipse. However, because the shadow cone has its own size on Earth’s ground, it must be considered between additional lines C2 and C3. Let’s assume that the C2 represents the 2nd contact on the ground and C3 the 3rd contact, respectively. As you can see, if these 2 lines are extended beyond the Moon towards the Sun, they determine the size of the Sun. From the observer’s point of view, the direction at which the 2nd contact is observed states the direction of umbra limitation, thereby the limit of the shadowed atmosphere. The same situation occurs at the opposite side of the umbral cone, at which the 3rd contact is observed. A similar situation has been explained here. The illustration below shows in detail how this effect is produced. The observer OM is placed at the end of line M (Pic. 4) (Sun-Moon-Earth) marked as T-OM, thereby at the centerline, at which the central eclipse is observed. In this case, the angular distance to the umbra limit, visible in the sky, is the same at least in 2 directions, C2-T and T-C3. From the perspective of observer O2, who is experiencing 2nd contact, he will see the shadowed sky C2-T-C3 limited to the line of C2. From the standpoint of observer O3, who is experiencing the 3rd contact, the circumstances will be opposite. In fact, the pattern shows the zenithal type of solar eclipse, but it can be applied easily to the horizontal circumstances (Pic. 2), where instead of A2 we can consider the C2 line tangent to the ground. If these circumstances come to pass, the observer standing on the ground and observing the 2nd contact exactly at sunset would see the umbra limit emerge at the horizon. Simultaneously, the same umbra comes up at the antisolar point. When the 2nd contact occurs below the horizon, the umbra at solar direction is not visible to the observer in a geometrical sense. However, the umbral boundary isn’t sharp. The image above (Pic. 3) represents the situation a second after the 2nd contact from the perspective of an observer located within the civil twilight zone. The smallest solar depression allows for earlier umbra visibility, limited to A1. Increasing solar depression means that the umbra eventually goes below the horizon at the same moment of eclipse. The observer will still clearly see the sudden darkening of the sky at solar azimuth, which is now projected by the largest deep partial solar eclipse magnitude (A2), but the increasing distance to the terminator also pushes it beyond the horizon. The increment of solar depression is inversely proportional to the level of sky illumination. In turn, the sudden darkening at solar azimuth becomes more pronounced as we approach the end of civil twilight. All the case studies represent the solar depression variations by only 0,5° for the same moment of eclipse. The beginning of totality at sunset doesn’t mean the same optical repercussions for the same time at the end of civil dusk (Pic. 7). An interesting phenomenon occurs at the same time around an antisolar point. Following image above (Pic. 3), if the point E represents the sunset at an altitude of 40km above the ground, it remains visible to the observer at various solar depressions. Even, if the true umbra remains under horizon at 2nd contact, from the perspective of point E it’s simply the beginnng of totality at sunset, to which apply all the rules explained above. Because the false umbra starts to appear at the 2nd contact, it will be visible at various altitudes above the antisolar horizon, following the position of the twilight wedge (Pic. 6)

The right sequence shows a significant impact of a deep partial solar eclipse at antisolar azimuth. The umbra is yet to emerge shortly just above the twilight wedge. The C.U. indicates the antisolar point, above which the shadow tends to emerge. The reason why the largest swath of darkness tends to be observed on the right (southwards) of the antisolar point will be explained in further reading, as it is related to the direction of umbra movement and Earth’s rotation. The optical appearance of the twilight wedge varies significantly between non-eclipse and eclipse conditions, although there is no difference in the changes in solar depression (Pic. 7,8).

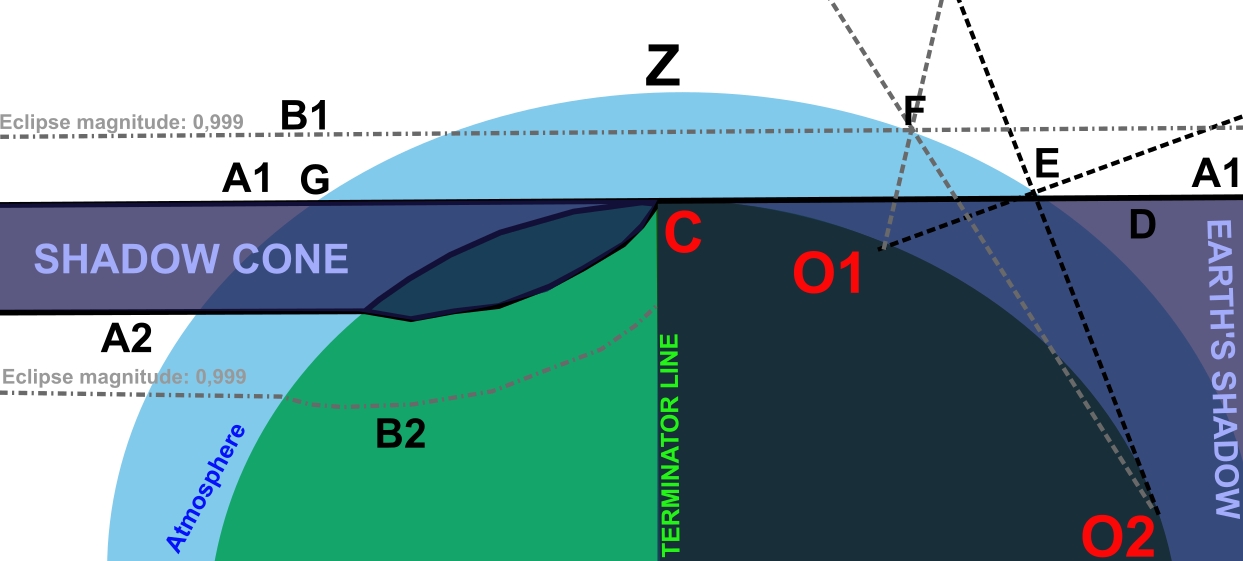

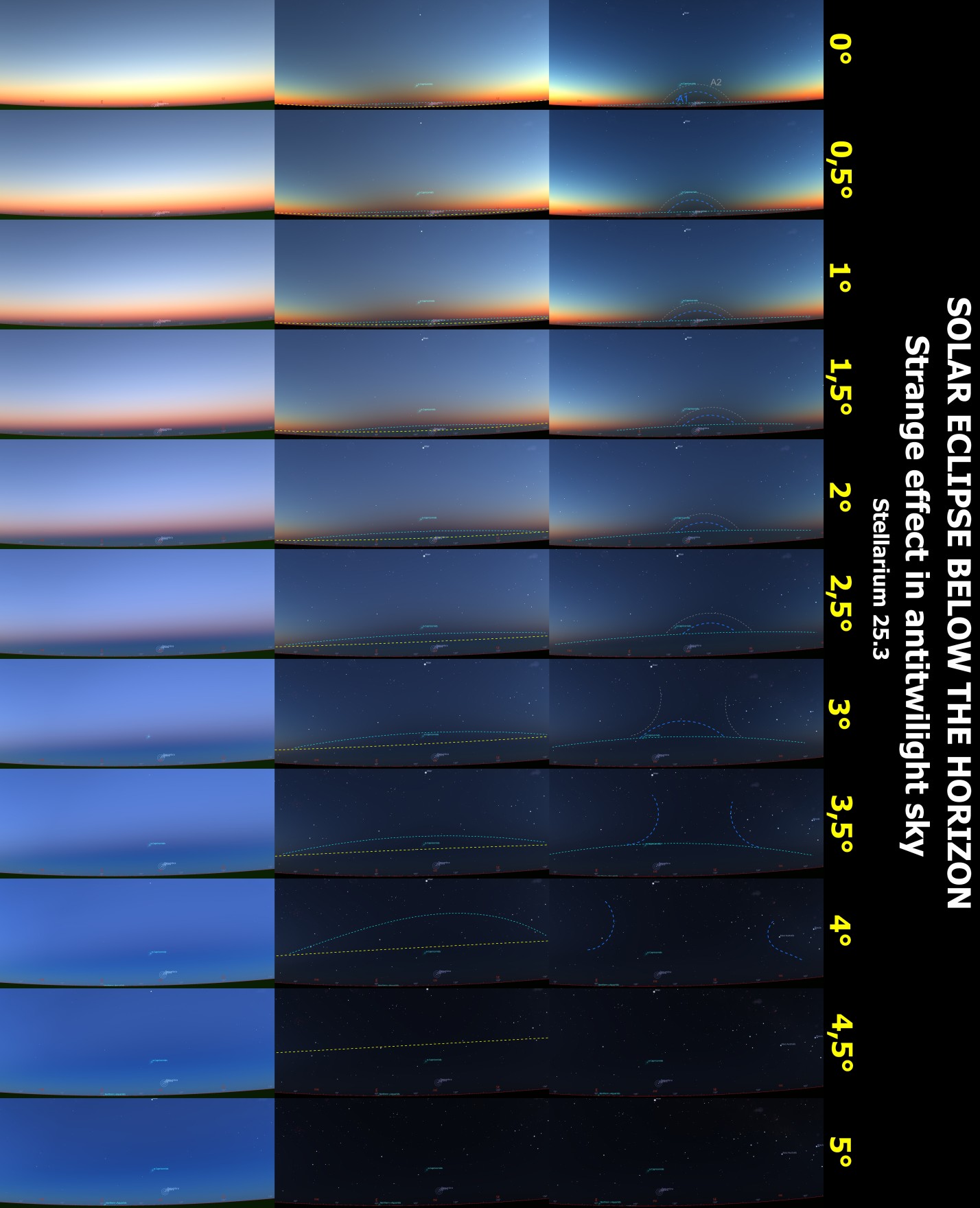

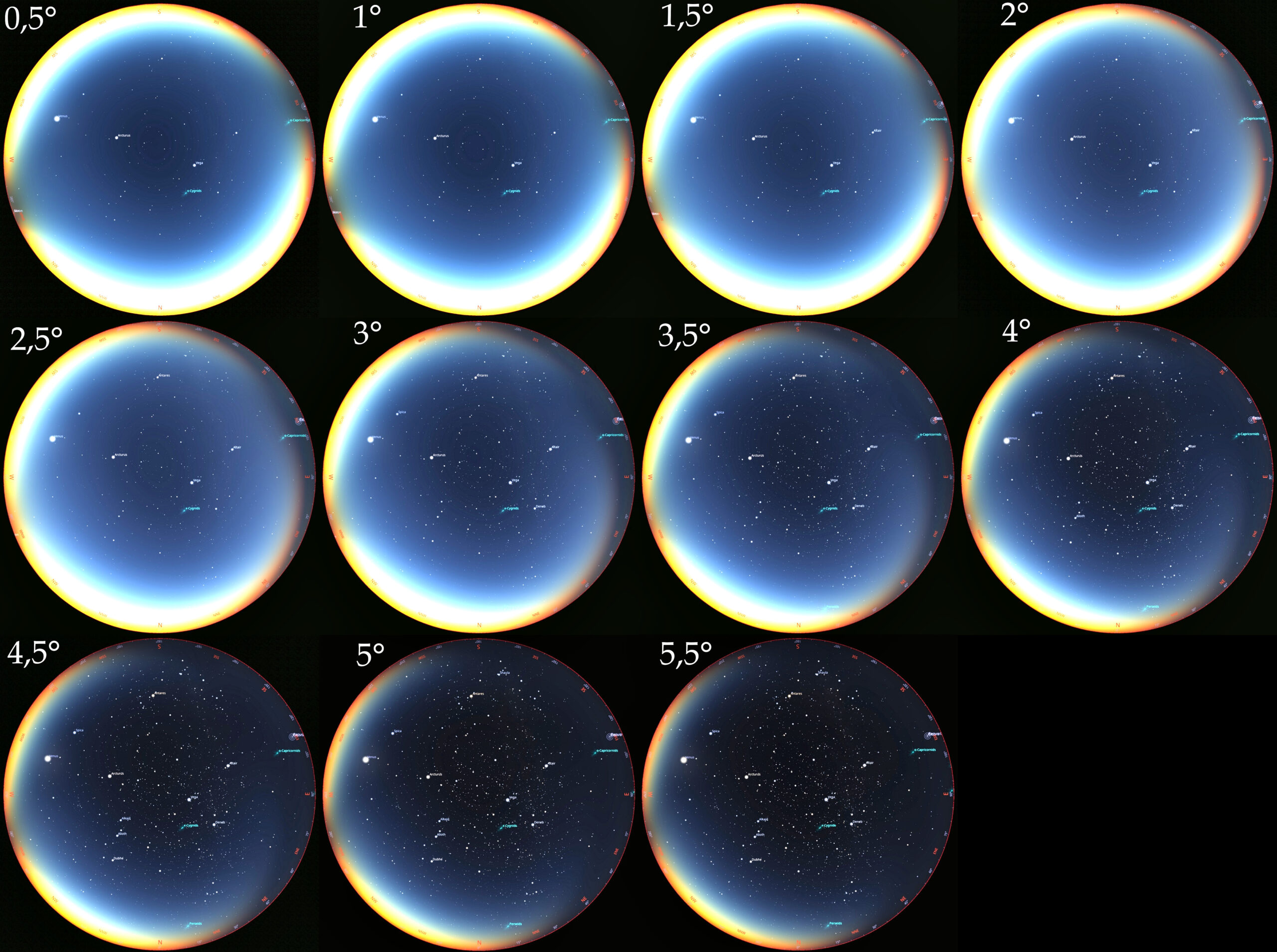

Looking at the three separate segments presented above (Pic. 7), there is a significant difference in sky illumination, which doesn’t facilitate the identification of the size of the solar eclipse’s impact on the antitwilight sky at larger solar depressions. We shall assume that at solar depression of 4,5° the twilight wedge is recognised as the faint bright line high above the horizon, in the middle of the frame. An additional increment by 0,5° shows that we are currently looking at the sky shadowed by the Earth, therefore no marks are required at other segments. Since the yellow dotted line indicates the typical position of the twilight wedge after sunset, the light blue line shows its position just before or after the beginning or end of totality, depending on when we are watching it. For the morning hours, such as this, it occurs at the very end of totality. The rightmost segment presents the moment at which the A1 edge of the umbra, discussed above (Pic. 2), is tangent to the ground. Then, the sunset observed from a ground-based perspective appears the same at the antisolar azimuth. The sky above is still outside the shadow, although the areas of equal eclipse magnitudes can outline its differences in illumination. For instance, as we assume the A2 known from above (Pic. 2), it outlines the direct vicinity of the shadow affected by the largest eclipse magnitude smaller than 1, thereby from that perspective the Baily’s beads are seen. Very interesting is the spectacle that occurs daily in the antitwilight sky. Within the changes of solar position from 1° above to 4° below the horizon, the antisolar half of the twilight sky features dynamic changes in colouration combined with rapid movement of the twilight wedge. It has been explained in this article, though only in terms of modelling. Considering the solar depression of 4°, which is marginal for the Belt of Venus appearance, it marks the moment of “handbook” division of the antitwilight sky into four major sections, as discussed earlier. The dynamics of optical changes at this stage of twilight are very interesting, even without the eclipse effect. As an additional element that contributes to this daily spectacle, the whole event can be extremely unusual, especially when the impact of a total solar eclipse is considered. Unfortunately, there are no observation reports of occurrences like this. The only reasonable approach to the scenario can be rendered by the Stellarium 25.3 ShowMySky mode, thanks to which we can easily imagine what to expect when standing at the geometrical extension of totality (Pic. 9).

The modelling above (Pic. 9) shows the impact of an almost-total solar eclipse on twilight at the moment, which limits the visibility of the Belt of Venus. The 2nd contact is yet to occur in the next few seconds. The geometrical approach of the “false umbra” (Pic. 2) is visible in darkening just above the antisolar azimuth. On the other hand, the distribution of the sky segments remains very similar. In definition, the Antitwilight Arch (AA) remains the brightest just outside of the umbral zone. However, the visibility of the umbra makes it difficult to point out the boundary with the Upper Sky (US). Unlike the Upper Sky (US), the boundary with Blue Band (BB) tends to be better expressed, probably because of atmospheric extinction of the weak light dimmed by deep partial eclipse. The most interesting is Horizontal Band (HB), which corresponds to the indirect sunlight scattering within the planetary boundary layer. A relatively high aerosol density makes this band brighter than the shadowed section of the sky beyond. Eventually, the lowest section of Horizontal Band (HB) at the horizon looks slightly dimmer, because of slight light depletion on its path through the lower troposphere. The approaching (or receding) total solar eclipse boosts this effect, especially at antisolar direction, which receives the lowest amount of scattered light from the Sun at this moment.

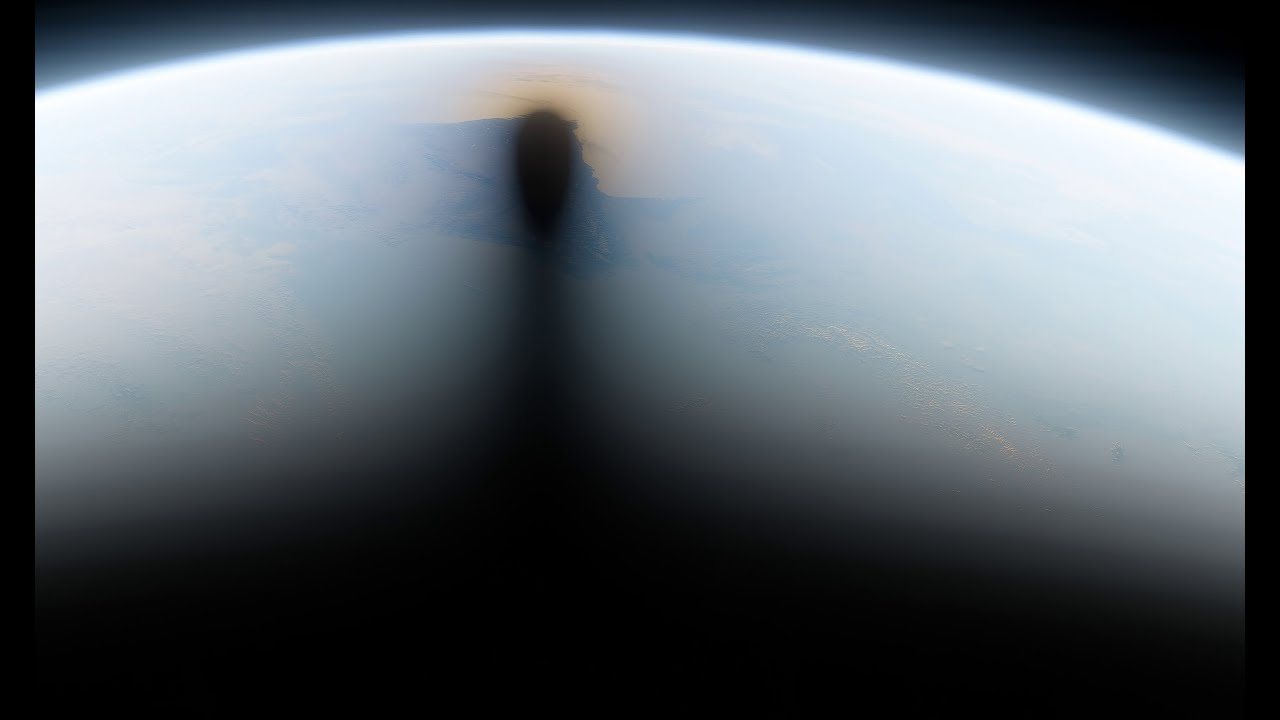

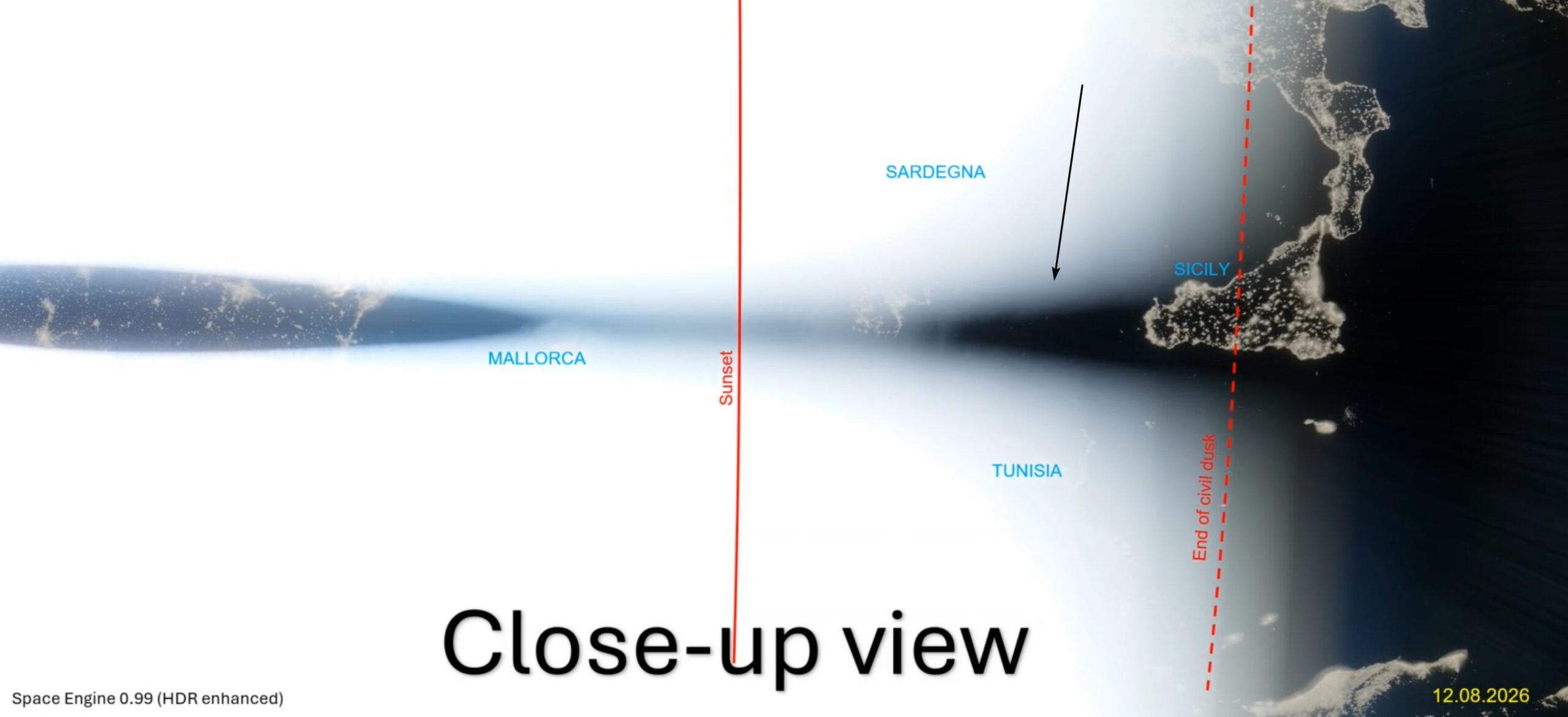

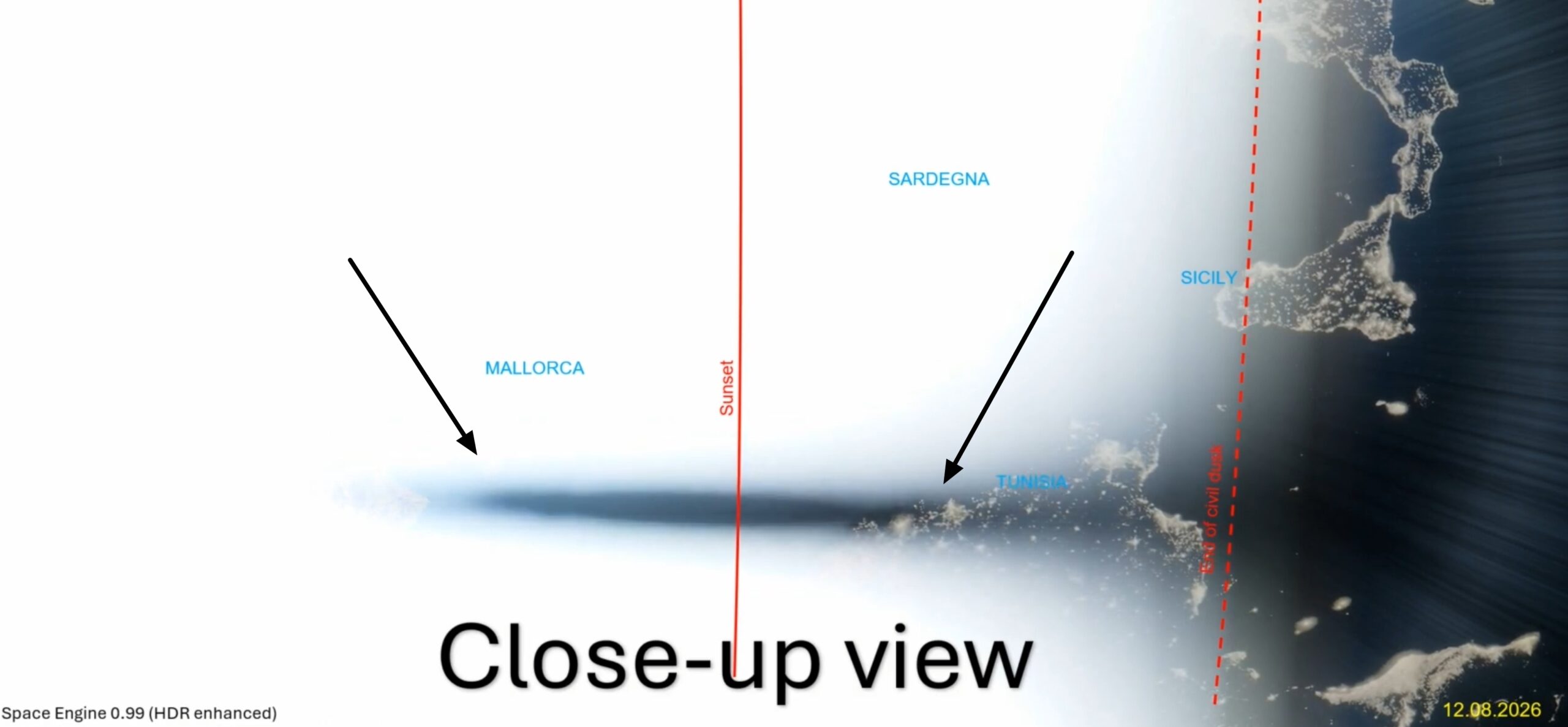

The same “false umbra” is much easier visible from space, although the continuation of darkness is also boosted by other, thrivial thing – the decrement of illumination level caused by increasing solar depression. It can be the primary reason for the bad interpretation of those events in the antisolar sky. Thanks to Space Engine 0.99, the following rendering (Pic. 10) was possible with the application of strong overexposure and HDR mode. The view such as this is not possible to obtain otherwise, because the terminator (Sunset) line usually is a division between the bright and dark sides of the globe. Considering any meteorological satellite imagery available to the public, likewise zoom.earth or sat24.com, the darkening approach fairly before the sunset occurs. Technically, it excludes a chance of a view such as this, and additional modelling is required. So far, the Space Engine software seems to be the best of them, because the drastic changes of settings allow us to render the view exceeding the zone of civil twilight. The terminator (Sunset) line is to be symmetrical to the umbra events which are about to occur and resemble the observer’s point C as explained in the pattern above (Pic. 2).

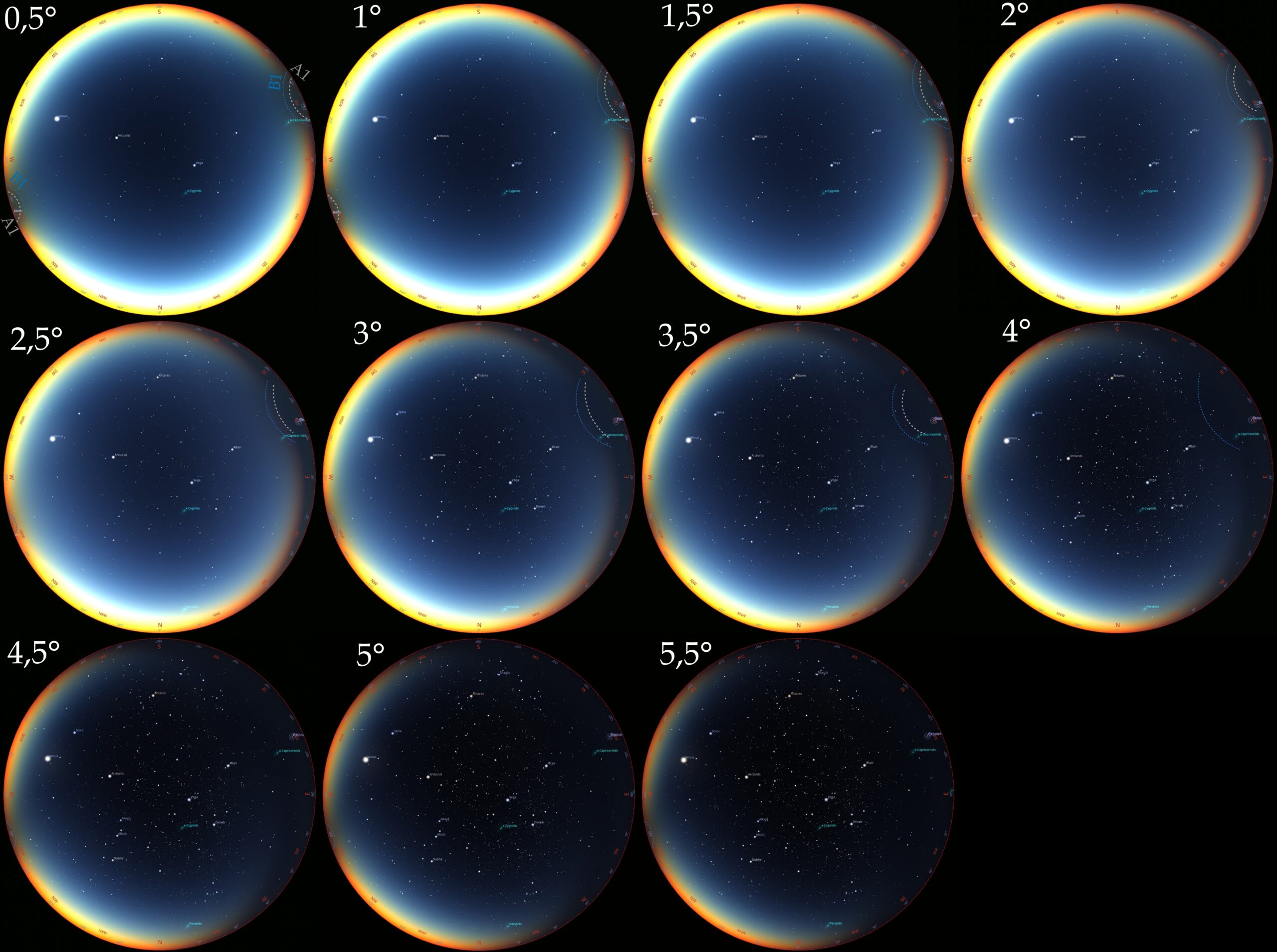

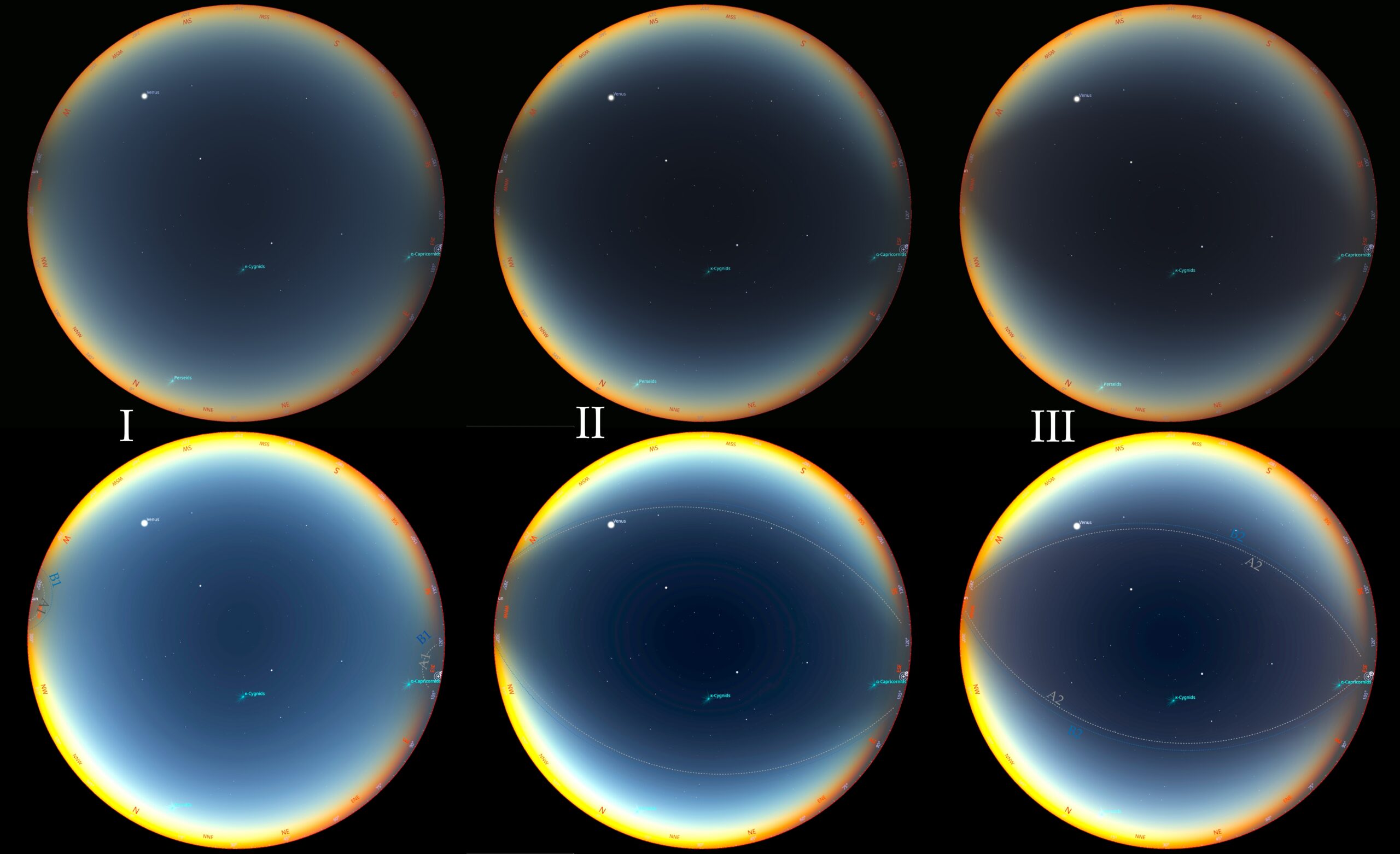

For summarising the section, which elaborates the umbra approach, noteworthy are all-sky views presented below with the breakdown of 0,5 degree (Pic. 11, 12).

The other, all-sky perspective view of the “strange effect” with a breakdown at 0,5° confirms the best visibility of the event at solar depression between 0,5 and 1,5°. Since only standard atmospheric refraction is taken into account, the smallest solar depression means that the totally eclipsed Sun right after the 2nd (or right before the 3rd contact at sunrise) is still partially visible at the geometric horizon. As the shadow proceeds with enormous speed, the analysed moment lasts probably no more than several seconds. Following Stellarium ShowMySky mode, an observer can expect up to 20-30 seconds of the event visibility if we assume the gradual darkening of the sky shortly before the 2nd (or after the 3rd) contact. As we know from many eclipses, it’s extremely hard to mark the exact boundary of the umbra. The transition between the illuminated and shadowed sky is sharp in daylight, when direct light scattering is at its peak. In contrast, twilight circumstances feature a slightly different scenario of the umbra event. The lack of direct sunlight scattering makes the umbra boundary fuzzier, and the entire effect seems to be optically extended regardless of the position of an observer against the terminator. When the eclipsed Sun is just below the horizon, the sky outside is still strongly illuminated. The presence of approaching umbra, which at this moment emerges from the horizon, produces a great contrast with sorrounding sky. The demarcation of the umbra boundary (A1) can be limited by the outline marked by the greatest eclipse magnitude smaller than 1 (B1), because even the greatest sharpness won’t show the abrupt cut out between the light and the shadow. This boundary always has some level of fuzziness, and the B1 outline is its apparent limitation, which depends on the human eye’s perception and is subjective. Because the light level decrement curve resembles the shape of a logarithmic function, the sharpness of the transition between the shadowed and illuminated sky decreases as we go outside of the umbra boundary (A1). Even if our sight is outside of the zone of greatest eclipse magnitude smaller than 1 (B1), notabene the zone of Baily’s beads appearance, we still can see a significant darkness against farther sections of the sky. At antisolar direction, high illumination plays a profound role in the Belt of Venus, where the colouration vanishes significantly. For deeper solar depressions, the real umbra boundary (A1) is not visible anymore at solar direction, although a lower level of illumination in the solar side of the sky makes the exact solar azimuth still dark enough to be considered as the limitation of the umbra. This particular area of the sky still has high contrast against the outside areas. Looking at antisolar direction, the determination of umbra limitations becomes harder when solar depression increases. There are 3 reasons behind it:

– The Belt of Venus fades out as the proportion of the colour band changes. It is briefly described in this article. Usually, when the Sun is 4° below the horizon, this effect is gone.

– The twilight wedge shifts up in the sky, which, by definition, is darker and results in changes of brightness distribution, which makes the effect appear larger than initially

– The sky gets darker in general, because it receives less direct sunlight in a whole sense.

As per the visualisations provided (Pic. 11, 12), we shall assume that the solar depression of 4,5° limits the visibility of the effect at a direction opposite to the Sun. It can’t be proved without on-site direct observation.

After the umbra becomes tangent to the Earth’s shadow, it moves through the atmosphere, shading it completely within a matter of seconds. The length of totality at the very end of its path is the shortest, as this point lies geometrically farthest from the Moon. The shadowed area on Earth’s surface shrinks until 3rd contact takes place (it occurs in reverse sequence at sunrise). The 3rd contact at sunset, and the 2nd one at sunrise, means that the inner boundary of the umbra (A2) has its most extreme contact with the Earth’s surface. At this moment, there is no completely shadowed region on Earth’s surface, except for the point C. Directly after the 3rd contact (or before the 2nd contact at sunrise), the Moon casts the shadow solely into the Earth’s atmosphere, although again, this moment ends up within a second. The specific circumstances under which the shadow cone affects the Earth’s atmosphere without the ground are presented in another pattern below (Pic. 13).

Another extremely elusive moment applies the nearest vicinity of umbra, which, in fact, affects the Earth’s atmosphere only. From the perspective of the ground observer at point C, the Baily’s Beads are seen, whereas 30-40 km above his head, the totality occurs. It’s a classical situation at the very beginning and the end of every path of totality, although much harder to be detected by the observer itself. He sees the zenith sky as the darkest section in any conditions, even if shadowed by the umbra, it might not present any visual difference for him. However, as per Stellarium’s ShowMySky modelling, some asymmetry in the sky surface brightness distribution can be observed at the antisolar direction (Pic. 14).

From the perspective of an observer, located within early civil twilight, the twilight wedge appears to look separated from the umbra. A soft band is noticeable between the lower sky, shadowed by the Earth, and the upper sky, shadowed by the Moon. The band results from the Belt of Venus appearance, which is most prominent at solar depression of about 1,5-2° and varies significantly across the sky in colour and brightness. This is an exact element, which makes the “strange effect” visible well at antisolar azimuth. For an observer located at point C, the twilight wedge isn’t visible, as he stands at the geometrical terminator line. However, the rising antitwilight arch reveals the faint limitation of the umbra. The event is very elusive and hard to notice properly, from that location, as the lowest section of sky becomes brighter along with the gradual restoration of the Belt of Venus colouration. The umbra limit will be undefined in the upper sky, because it’s typically darker as we move our sight towards the zenith. The solar direction doesn’t give the view of this effect (Pic. 15), because there is no sky shadowed by the Earth at all.

In exchange for antitwilight optical phenomena, an observer standing just behind the terminator line can notice the mirror-like umbra end caused by light extinction at the lower atmosphere. This event is mentioned in this article when modelling the sky surface brightness distribution. According to Rozenberg, the brightest section of the sky at solar azimuth doesn’t lie directly on the horizon, but is slightly above due to the extinction. Therefore, the brightest point of the solar section of the sky is usually observed a couple of degrees above the horizon line. In the case of additional affections, as a total solar (or deep partial/annular) eclipse event, the brightest section of the sky is observed at a slightly different direction. Following the recent modelling and assuming a hypothetical observer position exactly at the extension of the eclipse path, we shall assume that the brightest sections of the sky are distributed evenly on both sides of the umbra. The image above (Pic. 15) shows an idealised view of this situation as the total solar eclipse approaches its end on the ground. The same as in the opposite direction, the boundary of the umbra is hard to define, especially since the horizon sky tends to be brighter within the Moon’s shadow. This is because, as mentioned earlier, the apparent brightness of a totally eclipsed Sun is approximately -16 Mag, which makes it almost 23x brighter than the full Moon at perigee. Despite much brighter sections of the sky placed outside of the umbra, the illumination of the shadowed region is a result of direct illumination of the totally eclipsed Sun and scattered light coming from outer areas.

Considering the view from the space, the umbra egress is clearly visible at the terminator line (Pic. 16, 17), confirming the pattern presented above (Pic. 13).

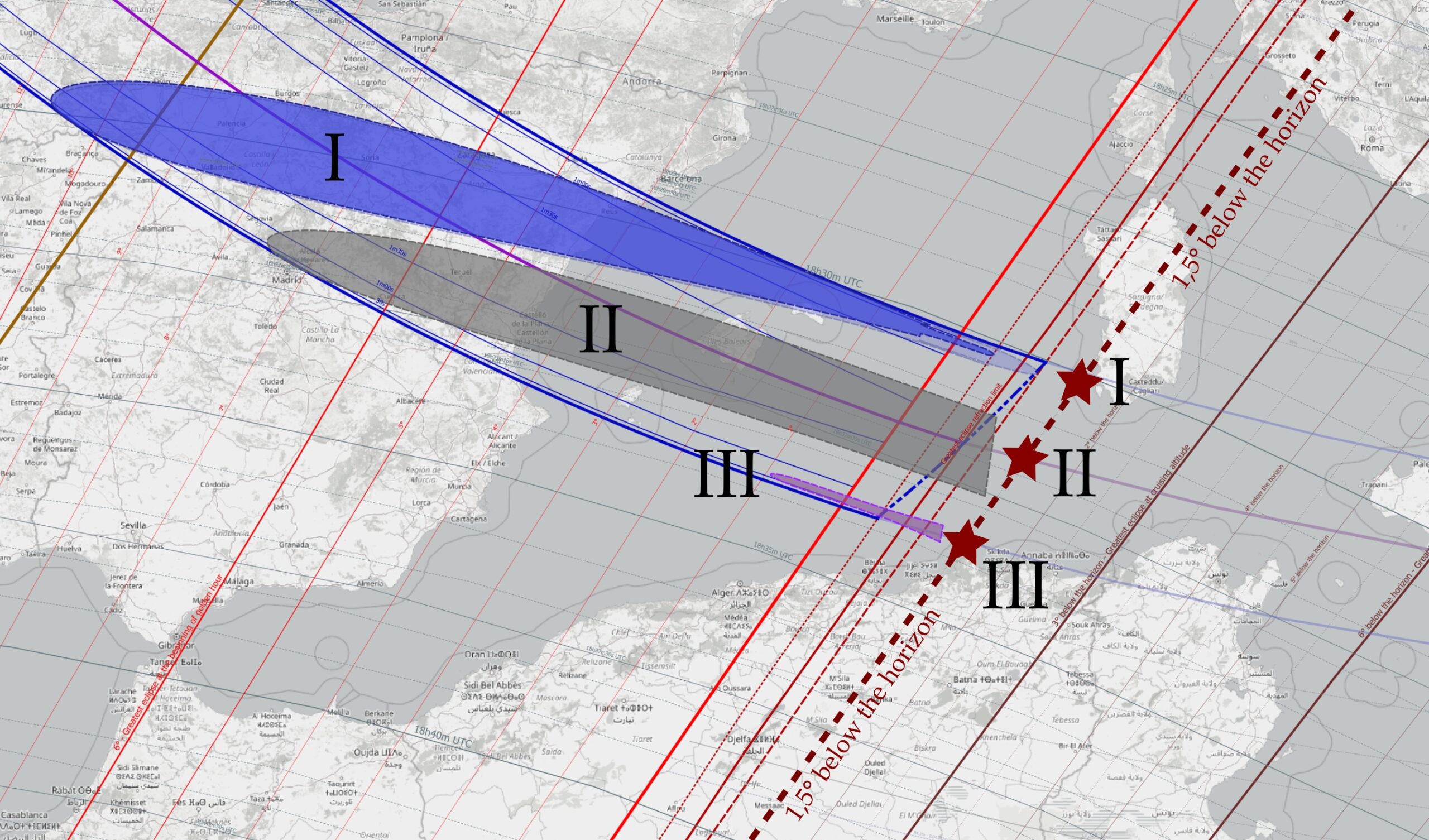

Analyses of the “strange effect” at two extreme moments of a total solar eclipse below the horizon lead to the final conclusion, in which the general shape of the umbra and its distribution over the sky are projected. Considering the August 12, 2026, total solar eclipse extension at the Mediterranean (Pic. 18), we can imagine three observers located in the places that correspond to the major moments of the eclipse event, where:

I – northernmost limitation – umbra ingress at solar azimuth

II – central line – the mid-eclipse umbra projection below the horizon

III – southernmost limitation – umbra egress at solar azimuth

Because of the atmospheric refraction, which lifts up the celestial objects by 35′ at the horizon line, the situation projected at the place I can be complicated. A geometrical sunset occurs realistically when the whole solar disk is still above the horizon. If the 2nd contact takes place at this moment, it refers to both the terminator as well as the dotted line marking the solar depression of 35′. From a geometrical point of view, the 2nd contact at the dotted line (solar depression of 35′) should occur a tad quicker due to Earth’s curvature. Moreover, the sunset ends when the upper edge of the solar disk disappears behind the horizon. It would happen at solar depression of 16′, but because of astronomical refraction, it occurs at true solar depression of 51′. The terminator line means that half of the solar disk is still above the horizon. The dual projection of the umbra means the correction in projection, because the 2nd contact should happen simultaneously in any place between the terminator line, when the entire Sun is visible and the place at which the upper disk of the Sun goes under the horizon.

All the cases have their own repercussions regarding the umbra’s position in the sky. Refraction also affects the horizon at antisolar azimuth, which tends to boost the “strange effect” slightly. On the images below (Pic. 19, 20), as per the Stellarium ShowMySky mode, the umbra is projected at three major moments of totality within the twilight zone, at solar depression of 1,5°. The leftmost figure represents the ingress of the umbra at the terminator line, which is defined by the northernmost limitation of the totality path extension. The “strange effect” is clearly visible around the 2nd contact at sunset on both sides. If the eclipsed Sun were visible here, the observer would be able to see very extended Baily’s Beads, a typical view for the grazing zone. The umbra, in fact, emerges exactly at solar and antisolar azimuth, but quickly shifts southwards when rising in the sky. As the totality advances towards a maximum, the segment of the shadow doesn’t occupy solar azimuth and zenith anymore. It moves southwards. Completely opposite circumstances occur at rightmost image sequences. As they represent case III, in which the umbra finishes its journey on the ground, the observer would again see the extended Baily’s Beads when the Sun is visible, but unlike case I, the shadow approaching from the north is visible well until it reaches the line from solar azimuth through zenith to antosilar azimuth. Then it starts fade out, as the totality ends. For an observer standing in location III, the shadow appears as a thin oval across the zenith sky, with other directions brightening up. This is the southernmost limit of the extension of the totality.

The most trivial case is location II, which lies at the extended centerline, and the umbra across the sky is the best pronounced.

In any case, the umbra remains symmetrical to a point located at right angle against the Sun, which in practise, for a small solar depression like this, can be at zenith. This is surely the most extreme point on Earth’s surface, and the last port of call for the receding umbra. Along with changes in umbra position, there are noticeable shifts in colouration, which are caused by the situations described here and here. The last thing to mention is shown in the rightmost sequence. Some of you might ask, why the umbra remains still “integrated” with the horizon line at solar azimuth? The answer is really simple – it’s driven by the solar depression. The value of 1,5° is sufficient to tilt the umbra position and the entire “strange effect” as a whole, as per the breakdown presented in the previous illustrations (Pic. 7 – 12).

For a final summary, it would be good to look at the all-sky projections for all those locations (Pic. 19). The umbra is hardly detectable in the dark twilight sky, especially around the eclipse culmination.

The moment at which the lunar shadow is tangent to the Earth’s ground surely doesn’t mean the very end of solar eclipse circumstances. In a simplified sense, the Earth’s atmosphere can be considered semi-opaque, with some sunlight reflected and the rest passing through to the other side. The presence of Earth’s atmosphere helps us to understand the behaviour of the Moon’s shadow in the direct vicinity of our globe. The impact on the lowest part of the atmosphere, which is restricted to the altitude at which the daylight sky becomes black, results in various optical phenomena. However, the same pattern would apply to the upper sections of Earth’s atmosphere, whose changes aren’t readily apparent to the human eye but can have significant effects on other aspects. I primarily mean the influence of a solar eclipse on the ionosphere, which is being investigated only within the geometrically defined limitations of the Earth’s daylight side. Unfortunately, nobody addressed the changes triggered by the eclipse effect, which can be observed far from the geometrical path limitations. Since the optical-based atmospheric response reaches the horizon dip of 6 deg, which corresponds to a distance of about 600km beyond the geometrical eclipse limit. On other occasions, it would be good to consider the shadow’s size relative to various lengths of totality. For example, the umbra size observed in 2024 was larger than expected in 2026, where the totality duration at sunset will be shorter by about 40s.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

These projections wouldn’t be possible without the Stellarium ShowMySky mode, developed by the Stellarium Development Team, led by G. Zotti and A. Wolf, which produces the best simulated-sky software for open-source environments. Another sincere gratitude I would like to express to Vladimir Romanyuk, who developed another fantastic sky simulator – the Space Engine. With version 0.99, a user can simulate the solar eclipse views from various perspectives, including space. I would also like to thank Mateusz Kalisz, the leader of the AstroLife programme, who explained where to find the ShowMySky mode in Stellarium 0.23

Links:

References:

- Bruneton E., Neyret F., 2008, Precomputed Atmospheric Scattering, (in:) Eurographics Symposium on Rendering 2008, Volume 27, Number 4

- Meeus J., 2007, Mathematical Astronomy Morsels IV, Chapter 19, Willmann Bell Inc.

- Nufer R., 2011, There are solar eclipses with four strange effects, Robertnufer.ch

- Rozenberg G.V., 1966, Twilight – a study in atmospheric optics, Plenum Press, New York

Youtube: