The movement of prominences against the lunar disk during total solar eclipse

Except for many phenomena related to the total solar eclipse, that I observed away from the Sun there is one, which is worth attention. This is a prominences movement against the lunar disk, as we can observe during totality. As we know, everything moves in the sky. A fleeting solar eclipse is an effect of the lunar movement against the Sun. This movement can be observed as a change in the solar crescent. During the totality, the lunar movement can be noticed both by hiding and uncovering a solar chromosphere (which occurs just after the beginning and right before the end of the total phase) and by shifting prominences jutting from the dark lunar disk.

This is a very interesting event, quite easy to spot when looking at the Sun through binoculars or long lenses. These giant objects with a temperature of around 60000K and a typical size on the order of 100000 km. Sometimes the prominences may stretch across more than 500000 km of the solar limb (Mobberley, 2007). The biggest filament, observed in 2012 could have even 800000 km. Because the prominence is a large, bright, and gaseous formation extending outward the Sun’s surface they invariably show up bright against the dark sky background, as do flares (Tandberg-Hassen, 1995). Most of the prominences have a loop shape. Aside from the most extended prominences a big amount of quiescent prominences are to be seen around the solar limb. These prominences are long with sheet-like structures nearly vertical to the solar surface. Their dimensions are 60000-160000 km in length, 15000 – 100000 km in height, and 5000-15000 km in thickness (Tandberg-Hassen, 1995).

During total or deep annular eclipses, prominences are possible to see. They appear as pinkish plumes. It is really hard to spot it by the naked eye, thus small binoculars could be sufficient (Pic. 1).

Pic. 1 A big prominence jutting just before the 2017 annular solar eclipse in Argentina (credits: Glenn Schneider).

The longest prominences are rare, but when occur we can see them even for the entire totality (Pic. 2).

The example above shows the biggest prominence, seen during the 2017 total solar eclipse in Wyoming by PTMA (Polish Society of Amateur Astronomers) members. This prominence, marked by a solid line (Pic. 2) was visible throughout the entire totality and even tens of seconds before 2nd contact.

Pic. 2 The biggest prominence visibility during the 2017 total solar eclipse (credits: Artur Spaczyński, Marek Substyk, Agnieszka Nowak).

The moment after beginning and before finishing the total eclipse gives us the opportunity to see a lot of prominences surrounding the solar limb. Most of them, as remarked earlier are quiescent and can be seen as an additional, pinkish layer of the solar atmosphere. These prominences can be visible, especially during the slim total solar eclipses. Watching them during the Great American Eclipse and analyzing the photos from my colleagues I found, that less extended prominences hid behind the lunar disk 20 – 26 sec after 2nd contact and emerged on the opposite side at the same time before the end of the totality. These bigger ones were visible for the next tens of seconds up to mid-eclipse in places. Their movement against the lunar disk has been recorded by all members of the Great American Expedition, who used the Eclipse Orchestrator software. The easier way to record it is also placing the camera or camcorder (with a telephoto lens mounted) towards the eclipsed Sun for the entire totality. Below I gathered 6 pictures representing key moments of the 2017 total solar eclipse in Wyoming, which covered key moments, like the entire disappearing and reappearing of the solar chromosphere and a mid-eclipse period (Pic. 3).

Pic. 3 Key moments of shifting the solar chromosphere and prominences throughout the 2017 total solar eclipse in Wyoming (credits: Marek Substyk, Artur Spaczyński).

Stacking the picture above I was trying to use the pictures with as much similar exposure as I could. These images were produced with the Eclipse Orchestrator assists, which changes the EXIF data throughout the eclipse. Nevertheless, each image shows how quickly the appearance of pinkish elements of the solar atmosphere changes within this brief time.

As a summary of the Polish Society of Amateur Astronomers (PTMA) eclipse imagery, I collected every single photo next to each other as an entire result of the observation (Pic. 4).

Pic. 4 2017 Total solar eclipse prominences movement across the lunar disk captured by Polish Society of Amateur Astronomers (PTMA) members in Wyoming (credits: Artur Spaczyński, Agnieszka Nowak, Marek Substyk, Aleksander Knapik). Click to enlarge.

A swiftly changing prominence landscape throughout the totality was a result of the location, where the observation was carried out. Because all Polish Society of Amateur Astronomers (PTMA) members were placed almost roughly in the middle of the eclipse path (where the umbral depth reaches 100%), then everything was happening the quickest, as it could. Usually, in the middle of the path of totality, an observer has the least amount of time to enjoy both the diamond ring and the prominences. On the opposite side are observers watching the totality near the edge of the umbra, where these phenomena appear much longer. How can we explain it? I will write more about this in the future. Now, for the sake of simplification let’s take into account, that both Baily’s Beads and prominences appearance period is much longer at the umbral limit.

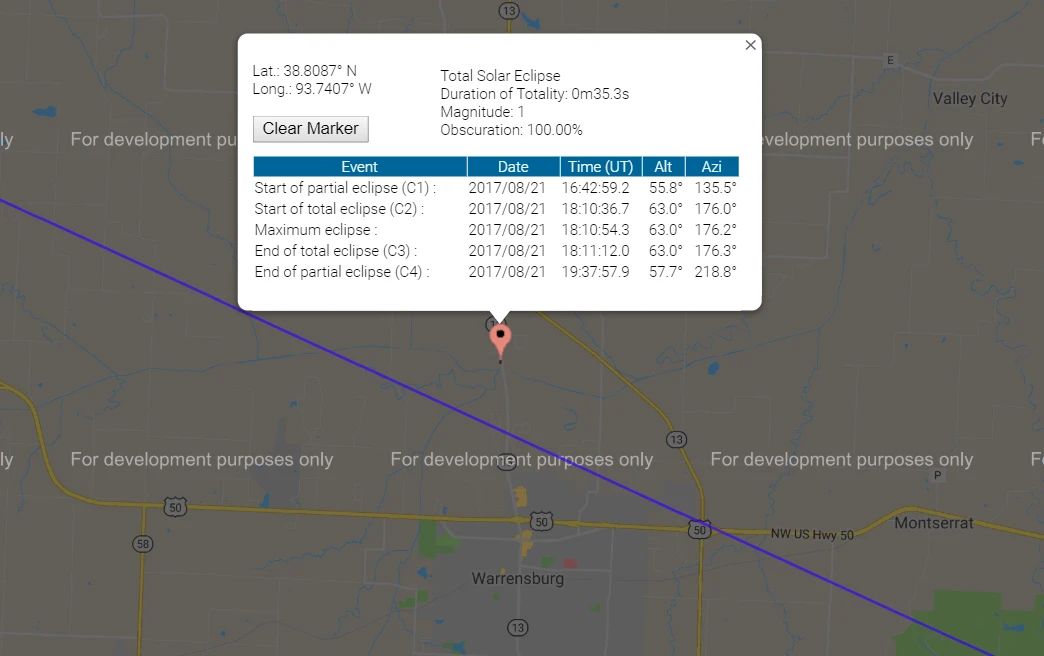

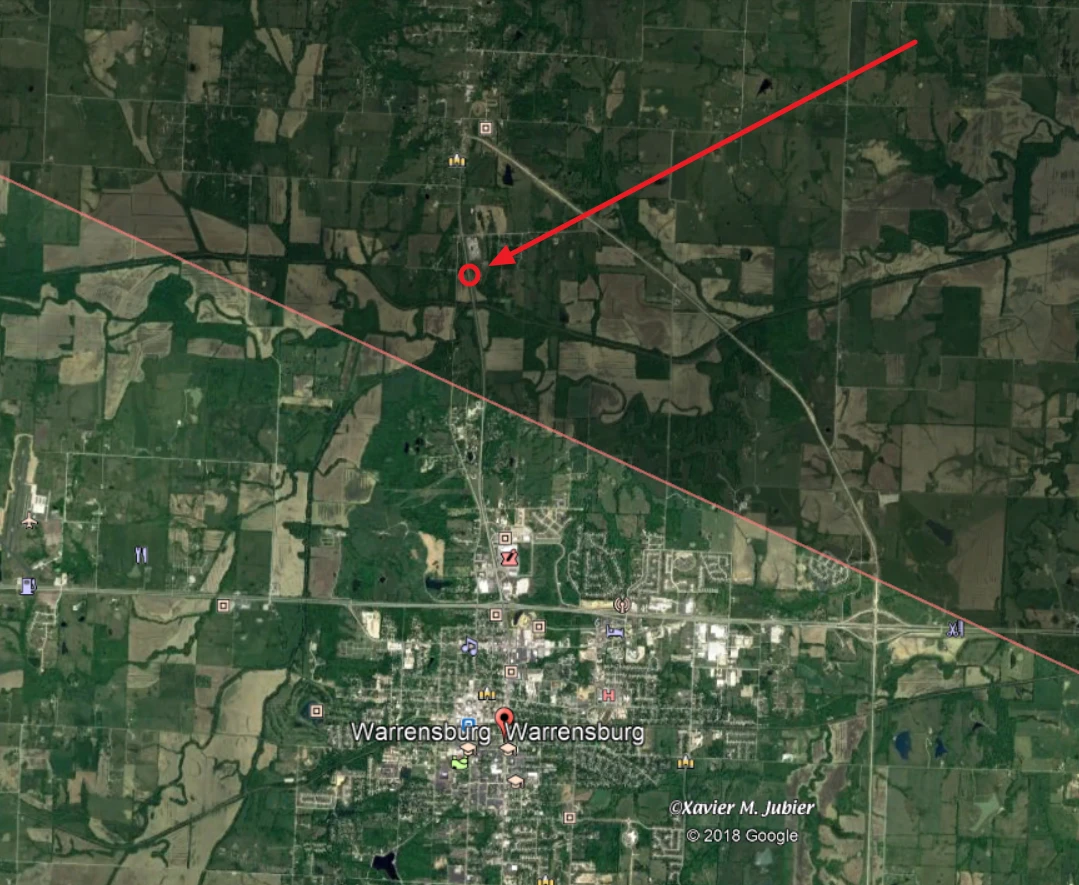

In the movie below you can see how “long” both Bailey’s beads and prominences with solar chromosphere are visible throughout the eclipse. The observation point was located only 1640 m from the southern umbral limit, just a bit north of Warrensburg, MO (Pic. 5).

Pic. 5,6 A presumed 2017 Great American Eclipse observation venue at the Warrensburg outskirts, MO, only 1,6 km from the southern umbral limit, where the duration of totality was about 35s as per Youtube footage (Eclipse.gfsc.nasa.gov, Xjubier.free.fr, Youtube.com).

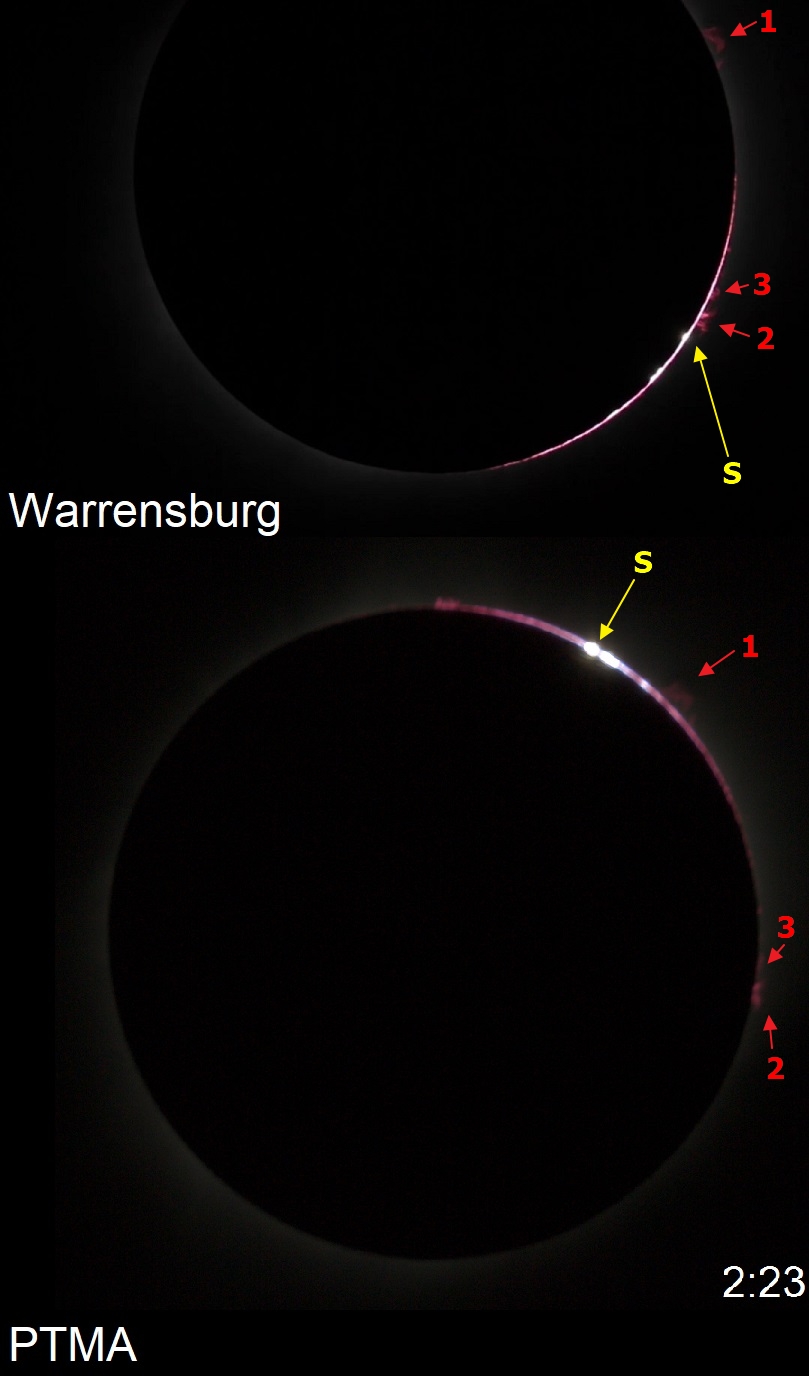

Pic. 7 A compilation of the 2017 total solar eclipse recorded at the Warrensburg outskirts, purportedly only 1640 m from the southern limit of totality, which lasted only 35 seconds. A red arrow shows a part of the biggest prominence as seen during this eclipse, which was rising above the lunar surface as the eclipse progressed. Click to enlarge.

Following the red arrow, you can also see how the prominence movement across the lunar disk. An amazing prominence-rise above the lunar surface has been covered by this footage as the totality progressed. Because the observation was taken near the southern limit, the brightest part of the totality occurs on the bottom side of the celestial disk.

An observation of the totality immediately beyond the umbral limit is preceded by long-lasting Baily’s beads, which start even more than 1 minute before through a slight fragmentation of the solar crescent, which next is separated on the single solar shafts, as seen in the picture above (Pic. 7).

There is still another important issue, that should be raised in this article. Namely, the “place” of 3rd contact against the visible prominences. It is driven by parallax phenomena and results in a different configuration of the first shaft of sunlight to that of the major prominences visible, which basically varies for every single location within the path of totality. For the sake of simplification, it looks different at the northern umbral limit, in the middle of the path, and at the southern limit (Pic. 8).

Pic. 8 A 3rd contact against visible prominences comparison between observations taken near the southern limit of the umbra at Warrenburg’s outskirts and near the middle of the path (Polish Society of Amateur Astronomers)(credits: Youtube.com, Agnieszka Nowak).

As you can see, the 3rd contact occurs in completely different regions of the lunar surface. It also incurs a different character of the diamond ring, being reliant on the lunar topography. Red numbers correspond to the prominence size, which was visible at that time. A number 1 indicates the biggest visible prominence, 2 – a 2nd one, etc. However, this is not authoritative enough, because footage from Warrensburg didn’t cover an upper part of the totality. The numbers have been used for exemplary reference. Anyhow, the difference is considerable. If we place another observer somewhere in the middle between these 2 places, then 3rd contact would occur somewhere between prominence 1 and 3. This is a good challenge for future eclipse observations – place a few observers in one line between the northern and southern umbral limit and do exactly the same observation. Threading this way we should gain an analogous prominence movement across the lunar disk caused by parallax instead of the celestial movement itself (however celestial movement is also related to parallax, which works differently here).

Mariusz Krukar

References:

1. Mobberley M., 2007, Solar eclipses and how to observe them, Springer, New York, USA

2. Tandberg-Hassen E., 1995, The nature of solar prominences, Springer Science + Business Media, Dordrecht

Links:

- Solar prominences – more information

- Solar flares and solar prominences

- Universetoday.com: Huge solar filament stretches across the Sun

Youtube:

Wiki: